TV Noir |

A CLASSIC CYCLE

|

77 Sunset Strip |

ABC 1958 – 1963

|

|

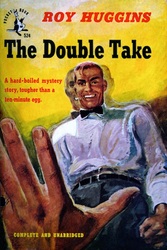

Like many aspiring writers of his generation, Roy Huggins worshipped at the altar of Raymond Chandler. The model for his debut novel, The Double Take, a febrile detective adventure set in Los Angeles and told in simile-laden first person, is about as inconspicuous as a tarantula on a slice of angel food cake. “I don’t know Roy Huggins and have never laid eyes on him,” Chandler wrote in a 1948 letter to his friend Clive Adams. “He sent me an autographed copy of his book with his apologies and the dedication he says the publishers would not let him put in. In writing to thank him I said his apologies were either unnecessary or inadequate and that I could name three or four writers who had gone as far as he had, without his frankness about it.”

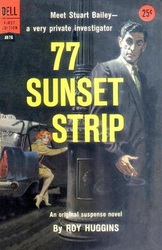

Huggins’s immediate sequels, the novelettes Now You See It and Appointment With Fear, both published in The Saturday Evening Post in 1946, expanded the debt. Broke, alcoholic, sarcastic, at odds with the police, misled by clients, never quite in the clear, Huggins's private-eye hero, Stuart Bailey, is an unabashed mimeograph of Chandler's most famous creation, Philip Marlowe. Which isn't to say that Huggins lacked the spark of originality, or that he had no business being published, but that every great writer needs a foundation from which to bloom. For the author of The Big Sleep, it had been Dashiell Hammett. For Huggins, who would go on to create not only 77 Sunset Strip, but Maverick, The Fugitive, and The Rockford Files, it was Chandler. The Double Take, once snapped up by Columbia, made Huggins a screenwriter. The resulting picture, released as I Love Trouble (1947), starred Franchot Tone as Bailey. Where the literary Bailey scratched the walls of a one-room flat with a pull-down bed, the filmic Bailey works out of a suite of offices; already, he's a little further up the social scale. Huggins, from the start, had real estate in mind. With 77 Sunset Strip, and the two pilots that preceded it, he further pushed Bailey out from Marlowe’s long and lonely shadow and into an arena of postwar affluence. His sardonic defenses replaced with an easy-going, man-about-Los Angeles air, the Bailey of television is as unflappable as he is upwardly mobile—a true Playboy-era detective. |

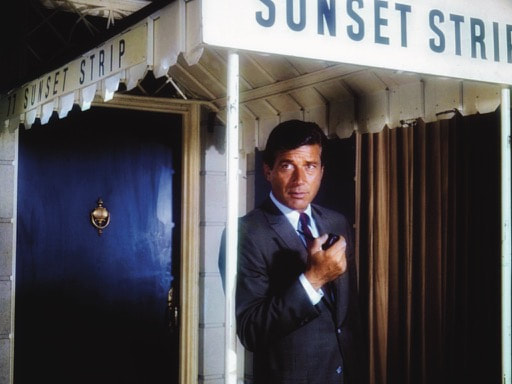

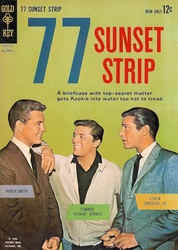

Publicity still for 77 Sunset Strip with Efrem Zimbalist, Jr. as Stuart Bailey, a private eye who claims his quarters on "the street that wears the fancy label / that's glorified in song and fable," as the title jingle went.

|

“He was so terribly Eastern—elegant, classy, the antithesis of the private eye. And I thought, what a great idea to cast this guy against the image of the hard-boiled private eye.” ✦ Roy Huggins

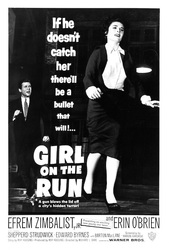

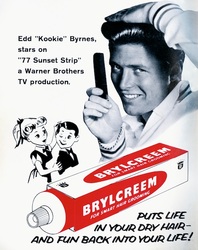

CLOCKWISE FROM LEFT: Artwork detail from "Appointment with Fear" (Roy Huggins, Saturday Evening Post, 1946; illus., George Englert). The first graphic representation of Stuart Bailey. • The Double Take (Roy Huggins, Pocket Books, 1946). A detective adventure "tougher than a ten-minute egg." • One-sheet for I Love Trouble (Columbia, 1947). Huggins loathed the re-titling: "A real detective never looks for trouble." • One-sheet for Girl on the Run (Warner Bros., 1958). Directed by Warners B-unit veteran Richard L. Bare, scripted by Roy Huggins and Marion Hargrove, the second pilot for 77 Sunset Strip was given a brief theatrical run. • 77 Sunset Strip (Roy Huggins, Dell, 1959). A paperback "original" stitched together from three of Huggins's Bailey stories. • 77 Sunset Strip (Gold Key, 1959). A wealth of cross-promotional opportunities ensured the wide demographic appeal sought by Warners and network partner ABC. • Advert for Brylcreem (ca. 1960) with Edd Byrnes. Bailey may have been the center attraction, but it was Kookie who brought in the Pepsi Generation. Byrnes's recording of "Kookie, Kookie, Give Me Your Comb" hit the top of the charts, while his public appearances attracted thousands of teenagers.