TV Noir |

NEO NOIR

|

Kolchak: The Night Stalker |

ABC 1972 – 1975

|

“They broke me down, broke my story down, telling me how it hadn’t happened the way I claimed.”

✦ CARL KOLCHAK

✦ CARL KOLCHAK

|

In Kolchak, a horror-noir hybrid, the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur, is given a paranoiac spin. Carl kolchak (Darren McGavin), our hero, is both a monster-slayer and an investigative journalist, two lines of work he’s compacted into one. Kolchak is forever on the scent of the big scoop that might return him to New York, where he was once a star reporter. exiled to the provinces, and hav- ing been fired from rags in Las Vegas and Seattle, he hangs his two-dollar hat at the Chicago outpost of the International News Service. It’s here, from a desk that rattles whenever the “L” thunders by, that he types up his encounters with things that go bump in the night. Handed over to his editor, Tony Vincenzo (Simon Oak- land), the irritable, close-minded type, Kolchak’s outlandish accounts induce yelling and ridicule, along with repeated suggestions that he seek “professional help”. “I expect you to report!” Vincenzo hollers. “Not to come up with fairy tales!” Myths and legends figure significantly in Kolchak’s adventures, for the monsters he encounters embody an ageless and pervasive fear of the dark.

As we learn in The Night Stalker (1972), the television movie that spawned the series, Kolchak has quite the knack for exposing what lurks in shadow, in this instance a centuries-old vampire on the loose in Las Vegas. When young women, all engaged in graveyard-shift casino jobs, begin appearing in the morgue drained of their blood, Kolchak wonders whether the culprit might be “some nutcase who’s seen too many vampire movies.” After witnessing the fanged, pale-faced, cape-clad suspect, Janos Skorzeny (Barry Atwater), survive two dozen gunshots while tossing scores of policemen around like pillows, he revises his theory: “I hate to say this, but it looks as if we have a real, live vampire on our hands.” Though Kolchak is correct, the authorities treat him with hostility, even as they remain stumped. So Kolchak, armed with a wooden stake and a sturdy mallet, takes it upon himself to track and slay the vampire. And for that, he’s run out of town. Kolchak finishes the film as he started it, alone in a dingy room, telling his incredible tale to his portable tape recorder. It’s a bitter pattern of triumph capped with defeat to be repeated through a sequel, The Night Strangler (1973), and twenty episodes of the subsequent series, officially titled Kolchak: The Night Stalker. Though Kolchak always vanquishes the monster, he can never overcome an inherently rotten establishment. Like Theseus, he’s fated to walk the labyrinth, only the thread meant to lead him out has instead been hung around his neck. Airing in the spring of 1972, The Night Stalker was seen by a record audience of seventy-five million. Its pitting of a truth-seeking, wisecracking everyman against the dual adversaries of fantastical evil and ruthless authority has ensured its cult status four decades on. While the vampire itself is pure Lugosi-kitsch, the world it terrorizes is recognizably contemporary and shamefully corrupt. This grounding of the outré within a shell of realism, while an integral part of Richard Matheson’s teleplay, was already imbedded in the source material, The Kolchak Papers, a then-unpublished manuscript by Jeff Rice, a reporter for a Las Vegas daily. Rice guised his novella as a work of nonfiction submitted by “an irascible second-rate journalist named Carl Kolchak.” Though Rice assures the reader that he’s verified Kolchak’s account as best he can, along with “cleaning up Kolchak’s language, much of which consisted of four-letter words,” already there’s a suggestion that Kolchak isn’t the most reliable of storytellers—an accusation he faces repeatedly in the series. Rice’s double epigraph for the book, memorably paraphrased in Matheon’s teleplay, outlines the terrain Kolchak occupies: Socially, a journalist fits in somewhere between a whore and a bartender. but spiritually he stands beside Galileo. He knows the world is round. —Sherman Reilly Duffy, Chicago Daily Journal Socially, I fit in just fine between the whore and the bartender—both are close friends. And I knew the world was round. I then discovered flat, and that there are things dark and terrible waiting just over the edge to reach out and snatch life from the unlucky wanderer. —Carl Kolchak, Las Vegas Daily News Aside from the vampire of the first tele-feature, and the 144-year-old serial killer of the second, Kolchak’s travels through the labyrinth bring him face-to- face with Jack the Ripper, a zombie, an invisible alien, a vampiric prostitute, a werewolf, a flaming specter, a satanic senatorial candidate, a shape-shifter, a swamp creature, an energy eater, a rakshasa, an android, a killer ape, a witch, a headless motorcyclist, a succubus, a mummy, a medieval knight, Helen of Troy (as a ghoul), and a primeval lizard. With each quest, Kolchak’s ability to function within the seemingly contradictory conceits of both “round” and “flat” enables him to serve as a superior investigator, yet his own accounting of each triumph, the story with which he hopes to restore his professional reputation, is invariably squashed, discredited, or debunked. As the mystery writer and critic Stuart M. Kaminsky has noted, “Though kolchak told the truth, he had to live with the pain of never being believed.” Because Kolchak’s narrative refutes the one put forth by the Establishment, he’s cast to the margins, isolated and made to look foolish and paranoid. |

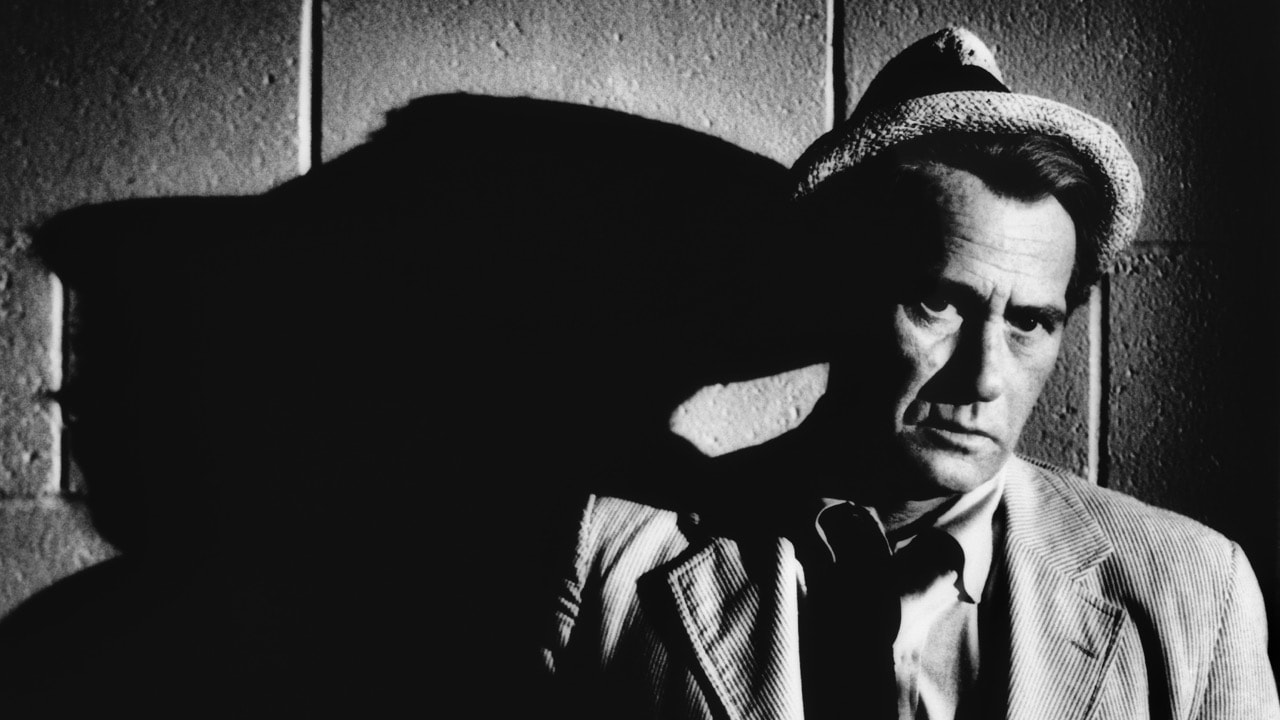

Promotional still for Kolchak (1972) with Darren McGavin.

The unnatural shadow cast by Kolchak suggests someone at odds with his surroundings and out of place in his time—an outsider hero. Early scripts had the character costumed in Bermuda shorts, a Hawaiian shirt, and baseball cap. “When I read that description I said, ‘No, no, wrong, wrong,’” McGavin recalled. “If that man is from New York and got fired in August 1965 and has been trying to get back ever since he probably hasn’t bought another suit since then.” CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT:

The Ripper (Kolchak, 1974). The Night Strangler (1973). The Knightly Murders (1975). In an era of political scandal and economic recession, Kolchak’s adversarial encounters with authority lent him considerable appeal. McGavin saw the character as “a folk hero battling the forces of evil we can’t put down ourselves.” Yet the outcome of such heroism is that while consistently proving himself a superior detective, he ends many an investigation in trouble with the law—blamed for all that’s gone wrong. Unreleased promotional still for Kolchak (1974) with Darren McGavin.

Hemmed in by strong midday shadows that contrast his signature summer suit, Kolchak waits for his train to come in. The industrial girding of the trestle, along with the repetitive slats of a platform that seems to stretch toward infinity, provide further motifs of entrapment and hopelessness. The sole prop—the camera in Kolchak’s hand—is also an emblem of futility. Though meant to document the unlikely truths he uncovers, it’s usually destroyed or confiscated before he can prove his theories correct. |

Abridged from TV NOIR by Allen Glover. Published by Abrams Press. All rights reserved.