TV Noir |

NEO NOIR

|

Harry O |

ABC 1973 – 1976

|

“What we have here is a show of the 1970s using a character of the 1940s.”

✦ DAVID JANSSEN

✦ DAVID JANSSEN

|

When David Janssen awoke on the morning of February 13, 1980, complaining of chest pains, his wife, Dani, phoned for an ambulance. By the time the paramedics arrived, it was too late: “Fugitive star, 48, dies of massive heart attack,” said the evening papers. Invariably, the fact that Janssen smoked and drank like a sailor on shore leave found its way into every obituary. What often got overlooked was that Janssen was a workhorse, an actor never on break. He spent the day before he died shooting a TV film. For four years, he devoted his entire waking life to The Fugitive. Barry Morse, his co-star on that show, described him as “the hardest-working actor there prob- ably has ever been in the whole history of television.” Harry O, in which he plays an aging, wincing private-eye with a bullet lodged near his spine, a part created for him by producer Howard Rodman, was his final series role. And for it, Janssen laid the bone-weary but persevering tally of his own life right on the counter, like a bar tab covered with too many cigarette burns and glass rings.

Circular marks are important in Harry O, beginning with the one in the title, an indicator of neutrality, but also the symbol of a cavity. As a detective, Orwell effects closure through discovery—clues, keys, secrets. He digs until the mystery ends. But he’s also driven by something more elusive, what Rodman, in his treatment for the series, described as “an unfulfilled inchoate hunger.” The centrality of a larger quest is made clear in Such Dust as Dreams Are Made On (1973), the first of two pilot films Rodman made with director Jerry Thorpe. It opens with a nighttime shot of Orwell’s raftered, unseaworthy boat, The Answer, the stenciled name of which is put forth like a title card. From this framing of the boat’s stern, as the camera pulls back through a window and slowly pans around a modest beach shack, what seemed to be an objective establishing shot becomes a gaze of subjectivity: this is somebody’s point of view. Not Orwell’s—he’s passed out, face down on the bed—but rather that of the lurking figure, features obscured, who takes a chair beside the unconscious detective. When the alarm clock that’s been ticking with growing urgency since the fade in goes off, Orwell is finally made aware of the gun aimed at him by the stranger in his room. yet he stays as is, flat and half-awake: STRANGER: I called the police to find you. ORWELL: I’m in the phone book. STRANGER: Well, they said they retired you four years ago on a line-of-duty disability pension. You got a bullet in you. ORWELL: What do you want? STRANGER: My name is Harlan Garrison. Doesn’t that mean any- thing to you? Well, about four years ago, on Friday, January eighteenth, around one-twenty a.m., you and another cop got a call on a burglary in progress at a drugstore. When you got there, there were two guys with guns. You got shot, and your partner was killed. I’m the guy that shot you. ORWELL: What do you want? Though Garrison (Martin Sheen), waving a fat stack of bills, offers to pay for an operation to have the bullet taken out of Orwell, there’s more to his visit than an exchange of cash for absolution. Three weeks back from Vietnam and already in a jam, he needs the services of a private-eye: “I want to hire you to help me find the guy I was in the drugstore with that night. He’s trying to kill me.” Orwell re- mains noncommittal, immobile; mostly, he wants to go back to sleep. Garrison persists. The war, he says, cleansed him of his taste for heroin, his criminal urges: “Who I am now and who I was when I shot you are two completely different guys.” One wonders whether Orwell feels the same disparity between then and now. Surely he didn’t live like this, alone, in near-squalor, prior to that night Garrison put a bullet in him. When Orwell at last makes a play for Garrison’s gun, he ends on his back like an overturned turtle. By the first commercial, he’s yet to stand on his feet. Soon enough, we’ll learn that this detective doesn’t even have a working automobile: he gets around Southern California on public transportation, which makes for some interesting detecting. Like much of 1970s neo noir, from Chinatown (1974) to The Long Goodbye (1975), Such Dust as Dreams Are Made On seems intent on demythifying its central archetype, or at least paring it to the root. Its very title returns us to the start of the classic cycle, to Humphrey Bogart’s famous line at the close of The Maltese Falcon (1941)—“The stuff that dreams are made of . . .”—while also alluding to Prospero’s summation of the human experience in Shakespeare’s The Tempest: “We are such stuff / As dreams are made on / And our little life / Is rounded with a sleep.” Along these contours, Rodman sets forth a detective-hero suspended between death and life, hence Thorpe’s oneiric staging of the introductory sequence as if it were an existential wake-up call. |

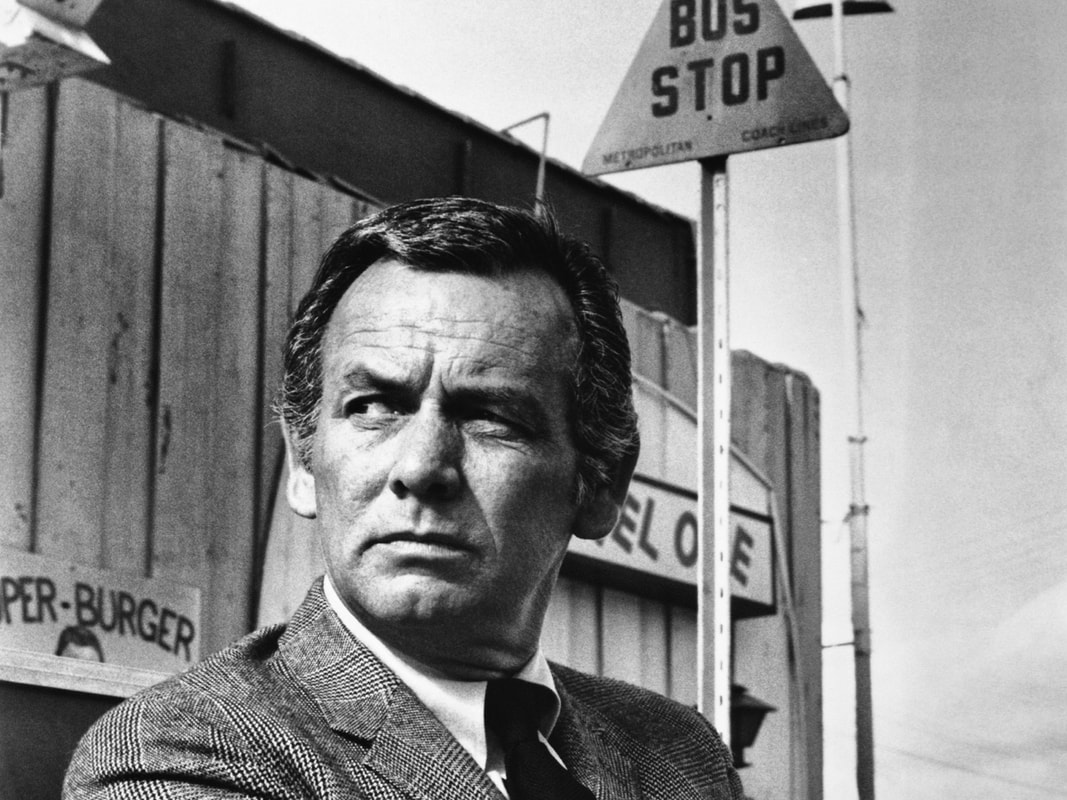

Promotional still for Harry O (1974) with David Janssen.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT:

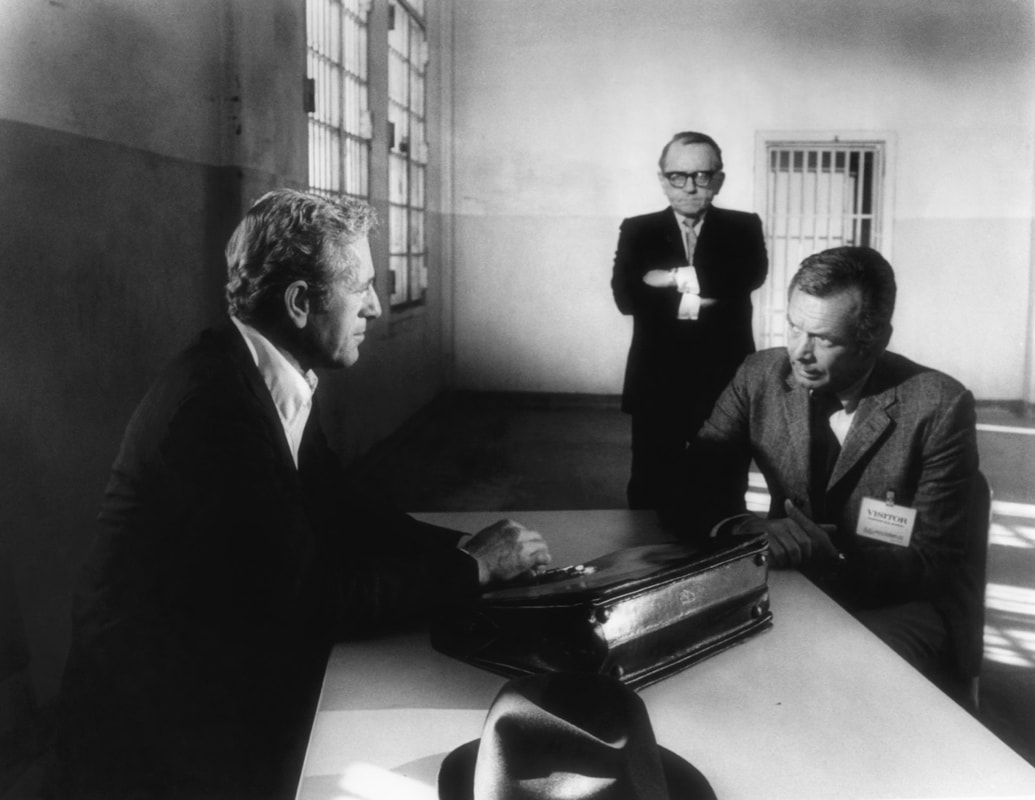

Such Dust As Dreams Are Made On (1973) with David Janssen; Kathy Lloyd and Martin Sheen; and Sal Mineo. The pilot film, written by Howard Rodman and directed by Jerry Thorpe, opens with Orwell roused from sleep by the junkie (Martin Sheen) who four years earlier put a bullet in his back. Smile, Jenny, You’re Dead (1974) with John Henderson, Martin Gabel, and David Janssen.

A second pilot film refined a compositional approach of which depth staging, forced perspective, and other visual tricks were paramount to shaping Orwell’s world. The bespectacled figure in the center, made smaller in scale by the use of a wide angle lens, provides an unsettling visual counterpoint to Orwell’s interview with a suspect. |

Abridged from TV NOIR by Allen Glover. Published by Abrams Press. All rights reserved.