TV Noir |

A CLASSIC CYCLE

|

Richard Diamond, Private Eye |

CBS 1957 – 1959

NBC 1959 – 1960 |

|

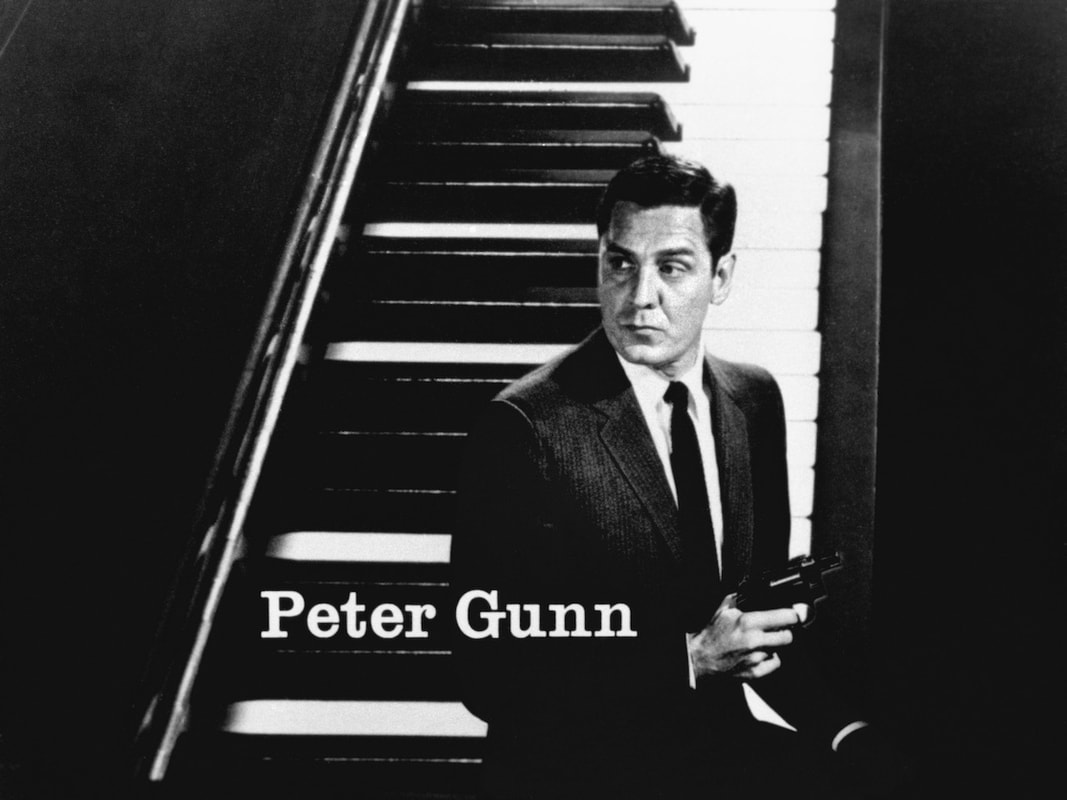

Peter Gunn

|

NBC 1958 – 1960

ABC 1960 – 1961 |

“Down these mean streets a man must go who himself is not mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid.”

✦ RAYMOND CHANDLER, The Simple Art of Murder

✦ RAYMOND CHANDLER, The Simple Art of Murder

|

At the time of his death in 1959, the most conspicuous evidence of Raymond Chandler’s considerable legacy was that television, a medium in perennial need of heroes, had endlessly mimeographed his iconic detective. The snappiest of the Philip Marlowe knock-offs rampaging through America’s living rooms that year were Richard Diamond and Peter Gunn. Both were devised by Blake Edwards, the former initially for radio (1949–1952), the latter expressly for television. Bridging the two is a telefilm iteration of Diamond produced by Dick Powell, who voiced the character on radio. The route from Marlowe to Gunn by way of two Diamonds underlines not only the elasticity of the prototype but the sustainability of the pervasively corrupt and nihilistic milieu Chandler outlined for his hero. While mostly stripped of the original’s melancholic world-weariness, the atomic-age clones share his disenchantment with the state of things, his need to rectify the ills of “a world gone wrong, a world in which, long before the atom bomb, civilization had created the machinery for its own destruction and was learning to use it with all the moronic delight of a gangster trying out his first machine gun,” as Chandler writes in Trouble Is My Business.

The radio Diamond is a singing detective. Powell plays him as an arch cynic, albeit one who celebrates the conclusion of a case by belting out a song or two from the hit parade. By 1949, Marlowe’s tenth year in books and the movies made from them, Chandler’s prototype had proved durable enough to be toyed with and riffed upon. Powell himself had contributed to the building of the myth as the screen’s first (official) Marlowe in Murder, My Sweet (1944), from Chandler’s 1940 novel Farewell, My Lovely. Visually, Edward Dymtryk’s film noir coalesced much of what is now celebrated as the noir style; narratively, it reinvented the detective film by presenting its protagonist as the interpreter of the action. Marlowe is introduced in a cellar where he’s been sequestered by the police. Blindfolded, he’s made to talk, and it’s through his lucid, sardonic narration, the filmic iteration of Chandler’s first-person prose, that the story emerges. Edwards, in developing Diamond for radio, drew heavily on this paradigm of the detective-hero as the appraiser of his own adventure—connecting the clues and commenting upon the progress of his own convoluted investigation. Notwithstanding its musical codas, Diamond was resoundingly violent radio. “In less than a year on the air,” reported Parade, “Powell has been slugged, shot, strangled, poisoned, knifed, heaved overboard, gassed and doped, crowned with crockery, and caressed with brass knuckles.” As many critics saw it, the hazard-laden Hammett-Chandler formula had already peaked by the end of the 1940s. Billboard opened its review by declaring that the “appeal of the hardboiled gumshoe type of whodunit, by now, is wearing thin, except to die-hard fans.” Few could have predicted the enduring, escalating popularity of the urban detective, not only in cinema and radio, but especially on television, where the private-eye would soon rival the western gunslinger as the medium’s preeminent hero. Stretching out into producing, Powell was among the first in Hollywood to get in on the telefilm market; his Four Star Productions was a leading supplier of filmed series in the 1950s, particularly anthologies. Eager to bring Diamond over from radio, but deeming himself unfit (“I can’t hold my stomach in for thirty-nine weeks”), he knighted the relatively unknown David Janssen. Richard Diamond, Private Detective debuted on CBS in 1957 as a thirteen-week summer replacement series. Janssen’s Diamond is a tough loner, capable yet frequently overwhelmed—a junior Marlowe. A former New York City cop who’s gone into business for himself, he’s also a slightly threadbare operative, hungry and lean, at least for the initial go-around. Edwards, meanwhile, having parted company with Powell, set to work on Peter Gunn, which arrived on NBC the following year. Gunn, played by Craig Stevens, and introduced with a walking bass and blaring trumpet that would make Henry Mancini a household name, is sleek and cocksure—a visceral man of action. “Gunn is a present-day soldier of fortune who has found himself a gimmick that pays him a very comfortable living,” Edwards explained. “The gimmick is trouble.” Like many writers of his generation, Edwards idolized Chandler—“my hero,” he liked to say. That trouble is the gimmick, or business, of the private-eye is, of course, a very Chandlerian view. Marlowe doesn’t want trouble, and certainly doesn’t initiate it, but once it arrives at his door or sits in his lap he isn’t left with much choice: his code dictates that he do what needs to be done to make it disappear. He exists to absolve others of the pickles that seem to accompany urban life. Take any Diamond (in either medium) or Gunn, and it becomes apparent how thoroughly ingrained Chandler’s design had become in the telling of detective stories from the 1940s on. Clichés and tropes persist because we expect them to be where they ought to be and function as they should, in the same way one automatically reaches for the light switch in a darkened room. So it goes that each episode of Diamond and Gunn adheres to a formula as melodic as the jingles that paid for their broadcast: a crime is committed, investigated, and resolved. Along the way, the detective interviews victims and witnesses; makes the rounds of lowlifes and likely suspects; is followed, bullied, thrashed, all the while enduring (and ignoring) repeated warnings not to poke around in other people’s affairs; arrives at a semi-resolution, sometimes in concert with the police, most often not; is promptly knocked out or otherwise incapacitated; comes to with renewed clarity; finds his way through the murky business at hand; and finally, violently, wraps everything up in a way that keeps the boys down at the morgue busy for the next week. Throughout this pattern of action and reaction, Diamond and Gunn, despite the preening presence of their counterparts in uniform, serve as the arbiters of justice: the rectifiers of the chaos that has ruffled the status quo. |

Murder, My Sweet (film, 1944) with Dick Powell.

Promotional still for Richard Diamond, Private Eye (radio, 1950)

with Dick Powell. Promotional still for Richard Diamond, Private Eye (1958)

with David Janssen. Network Interstitial for Peter Gunn (1958).

|

Abridged from TV NOIR by Allen Glover. Published by Abrams Press. All rights reserved.