TV Noir |

A CLASSIC CYCLE

|

Staccato |

NBC 1959—1960

|

“First of all, I don’t play a private eye. I’m a jazz pianist—that’s a hell of a lot of difference, pal.”

✦ JOHN CASSAVETES

✦ JOHN CASSAVETES

|

John Cassavetes was nearing thirty when he received the offer to play Johnny Staccato, jazz pianist and sometime private eye. After a successful decade in live television and a handful of “B” movies, the leap to leading man seemed overdue. yet the actor, who really wanted to be a director, had largely removed himself from industry call sheets to concentrate on the making of a self-financed, sixteen-millimeter film spun out of the acting workshop he ran on the side. Hustled together on the streets of New York with an amateur cast and crew, Shadows (1959) was a raw, strangely beatific, jazz-scored fuck-all to mainstream moviemaking. As it has since ascended to the pantheon of American independent cinema, the lingering consensus, particularly among those who view film as art and television as industry, is that Cassavetes took on Staccato purely for the paycheck. Why else, goes the reasoning, would the young rebel behind such a kinetic debut sully himself with a telefilm contract?

When the call came from Revue, the television wing of agency powerhouse MCA, Cassavetes was indeed broke from shooting and re-shooting Shadow. Moreover, he and wife Gena Rowlands were expecting their first child. Yet an editorial Cassavetes wrote for Film Culture around that time suggests that his motivation for accepting the role went beyond financial security. In his piece, titled, with characteristic insolence, “What’s Wrong with Hollywood,” he urges the town’s writers, directors, and actors to seize control of their art: “Without individual creative expression, we are left with a medium of irrelevant fantasies that can add nothing but slim diversion to an already diversified world. The answer cannot be left in the hands of the money men . . . the answer must come from the artist himself.” The appeal a weekly prime-time slot would have held for as ambitious and shrewd an iconoclast as Cassavetes can’t easily be dismissed. Shadows, as its director was the first to concede, had limited commercial prospects. Staccato, on the other hand, offered the chance to work the system from the inside. In his negotiations, Cassavetes made all the demands actors weren’t supposed to make. He wanted creative input, he wanted to name his own producer (Everett Chambers), and, most importantly, he wanted to direct—and he simply tore up every contract presented to him until he got his way. The show he joined had been in development for several years: its high-concept premise came out of a 1956 meeting between MCA chief Lew Wasserman, his lieutenant Jennings Lang, and the composer Elmer Bernstein, who was keen on scoring something for television. Though a pilot script, commissioned from Dick Berg, already existed, Cassavetes set to work reshaping his jazz detective into an artist-seeker whose innate humanism serves as his compass through a precarious noir landscape. Special attention was given to the dialogue, to the naturalistic cadences of how people on the margins, where niceties turn to dissonance, clarity to evasiveness, really articulate themselves. Cassavetes also sought to fill in the spaces of Staccato’s world, of which a boisterously sordid nightlife is an integral part. The noir city of Staccato bustles with sound—jazz, classical, rockabilly, even polka. Beginning with Bernstein’s jolting title theme, music pours from doorways and windows, cafes and nightclubs, tuning the viewer to the acoustics of a concentrated metropolis. The result is a milieu that neatly overlaps that of Shadows, and fully anticipates the setting of Too Late for Blues (1961), Cassavetes’s sophomore feature. Beyond asserting his vision of New York after dark, Cassavetes saw to it that Staccato tackled the sorts of hefty themes—payola, dope addiction, McCarthyism—that generally made advertisers squeamish. But it was his radical notion of downplaying the heroic qualities of his ambivalent private eye that would really raise the ire of the money men. The series, as Cassavetes would later explain, was doomed from the beginning by his urge to upend genre convention. “They felt that a show would have to be a detective show, strictly and absolutely with a hero,” he said. “I felt that my style is a human style. I’m a human being and I want to make mistakes just as well as solve the crimes; I want to not solve some crimes too.” On that last bit, there was much hair-pulling among the money men. |

Promotional still for Staccato (1960) with John Cassavetes.

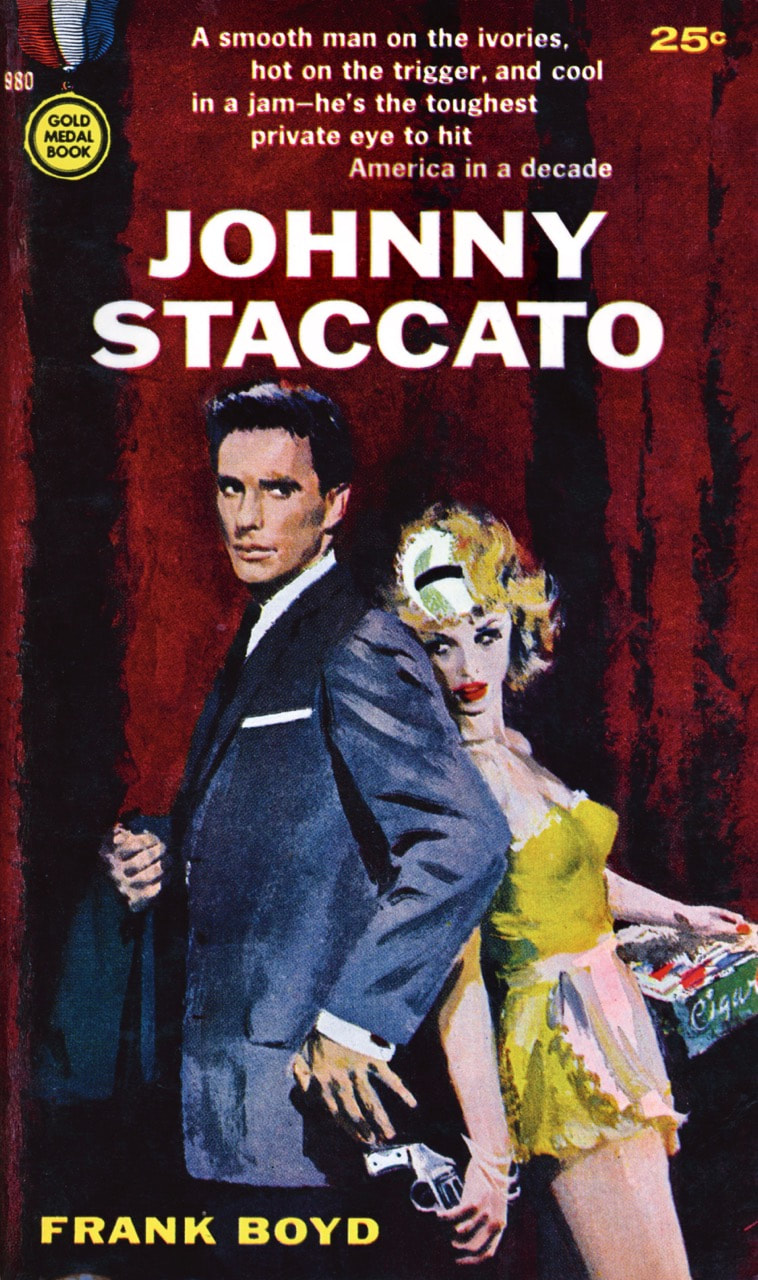

Johnny Staccato by Frank Boyd (Gold Medal, 1960). Boyd was the pen name of pulp novelist Frank Kane, a prolific writer of noir mysteries .

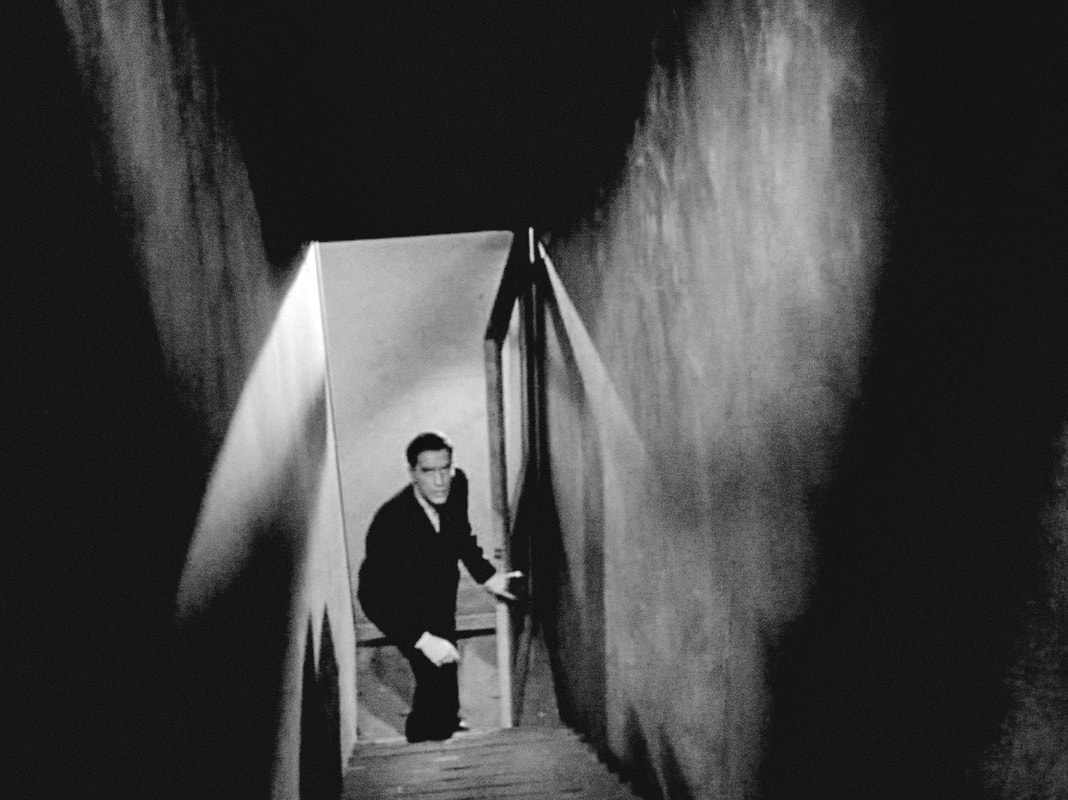

Night of Jeopardy (Staccato, 1960) with John Cassavetes.

|

Abridged from TV NOIR by Allen Glover. Published by Abrams Press. All rights reserved.