TV Noir |

NEO NOIR

|

The Invaders |

ABC 1967 – 1968

|

“Who are the invaders? you could have been riding in the bus with one of them this morning and never suspected it.

The postman might be one of them. Your dentist, too. Or your barber. You might be having lunch with one today.

And it’s just possible you may kiss one of them tonight.”

✦ ABC PRESS RELEASE, 1968

The postman might be one of them. Your dentist, too. Or your barber. You might be having lunch with one today.

And it’s just possible you may kiss one of them tonight.”

✦ ABC PRESS RELEASE, 1968

|

David Vincent, the loner hero of The Invaders, is presented to us right at the moment of his entry to the noir world. It’s a scene drenched in menacing iconography: from the pitch blackness, a pair of headlamps emerge to reveal a misty, lost highway while a narrator solemnly intones, “How does a nightmare begin?” For Vincent (Roy Thinnes), it begins with an ill-advised turn off the main road in pursuit of an all-night diner. Arriving at an establishment long since deserted, he shuts off his engine and allows his eyes to roll shut. Whirring sounds and flashing lights rouse him from his nap: he awakens with a front-row view of a flying saucer descending from the sky. Like any sensible citizen, he runs to the police, only to be met with derision. Persisting with his claims, he’s cast to the margins: no one wants to hear his theories about space invaders. Vincent clamors on, determined to prove that what he’s witnessed is the first flash of the end of days—a full-on colon-ization of earth.

Vincent’s quest is inexorably complicated by the deceptiveness of the invaders, who have disguised themselves in human form and infested every layer of society. They are, for the most part, indistinguishable from the regular citizenry—a fully assimilated enemy. Vincent learns this straightaway in episode one (“Beachhead”) when a sweet motel clerk (Diane Baker) to whom he turns for help reveals herself to be one of Them. “Don’t fight us,” she suggests. “It’s going to happen; you can’t stop it.” Having presumed he was in human company, Vincent can only shrink in horror and run for the door. Thereafter, he compulsively scrutinizes everyone he meets for signifiers of alienness, namely a mutated pinkie, but also a lack of heartbeat or pulse (and a correspondingly cold demeanor), only to discover that such characteristics are not shared by all aliens. While singular in purpose, the invaders are as diverse a “people” as the humans they intend to destroy. To create space for their own kind, they come up with all manner of calamitous, Lebensraum-minded schemes, from speeding along climate change (“Storm”) to breeding hordes of flesh-eating butterflies (“Nightmare”), all of which Vincent, in the absence of any official response, is impelled to thwart on his own. And when he does manage to corner or kill an alien, it dematerializes in a flash, leaving nothing behind. His is a confounding crusade. Because of the ridicule he invites with his doomsday message, Vincent is neither one of Them nor one of Us, but rather an outcast, a branded figure. In this he follows the legacy of innumerable noir protagonists whose complacency is upended without warning. “It’s funny how a man’s life can change so fast,” Vincent says in “Beachhead.” “After I saw that saucer, it seems as though I’ve been cut off from everything piece by piece.” His fatalistic observation echoes the words uttered by Al Roberts in Detour (1945): “From then on, something else stepped in and shunted me off to a different destination than the one I’d picked for myself.” It’s perhaps no coincidence that an all-night diner, that bastion of noir geography, figures centrally in the destinies of both men. This is where each first steps into the shoes of noir’s “wrong man,” a type characterized by Foster Hirsch in The Dark Side of the Screen as “a plaything of malevolent noir fate” for whom “a single misstep can precipitate disaster.” Al Roberts, for all his complaints about the finger of fate, is an unreliable storyteller. The journey he relates is less determined by “something else” than it is by his own masochistic curiosity. Vincent, too, exhibits this trait, though his tale is at least legitimized by the observations of the neutral yet authoritative Narrator (Bill Woodson), who concludes “Beachhead” with the observation, “How does a nightmare end? Perhaps, for David Vincent, it will never end.” Detail, The Invaders Comic No. 2 (1967).

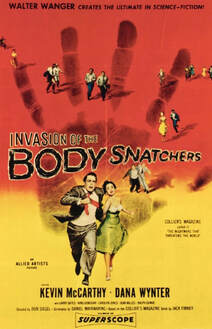

Poster for Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956). A common trope of Cold War sci-fi is that "aliens" are already among us--spouses, business partners, trusted members of the community. |

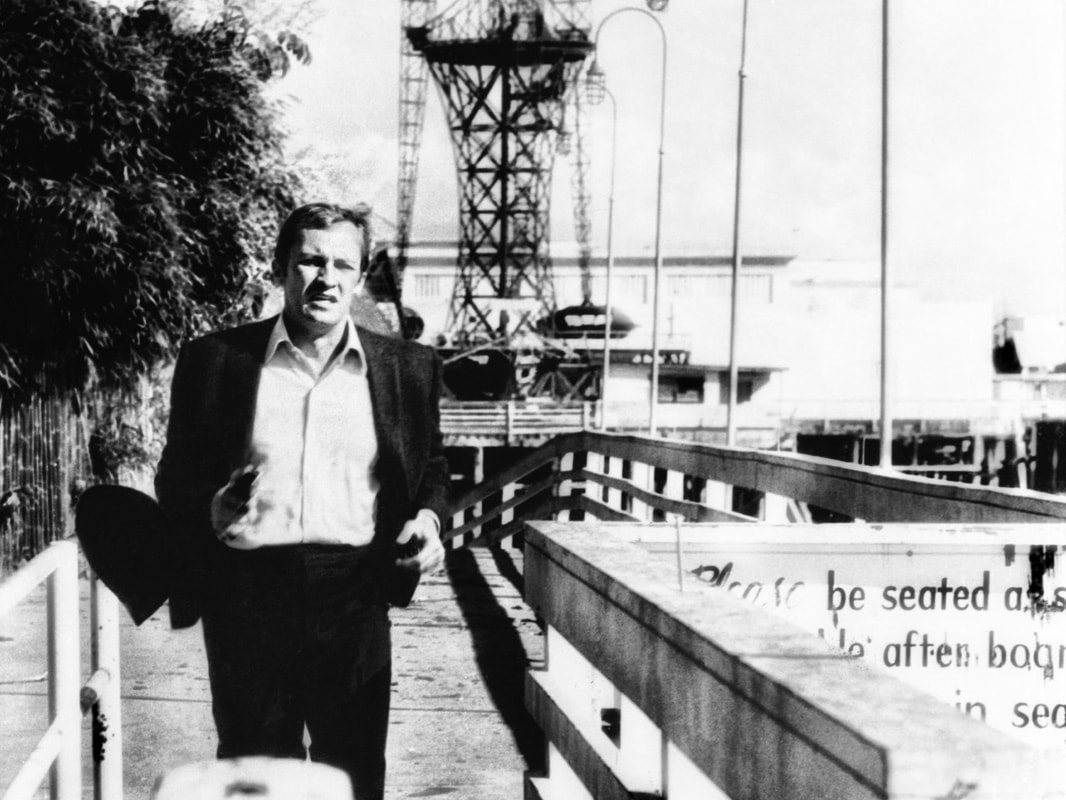

The Ivy Curtain (The Invaders, 1967) with Roy Thinnes as David Vincent.

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP:

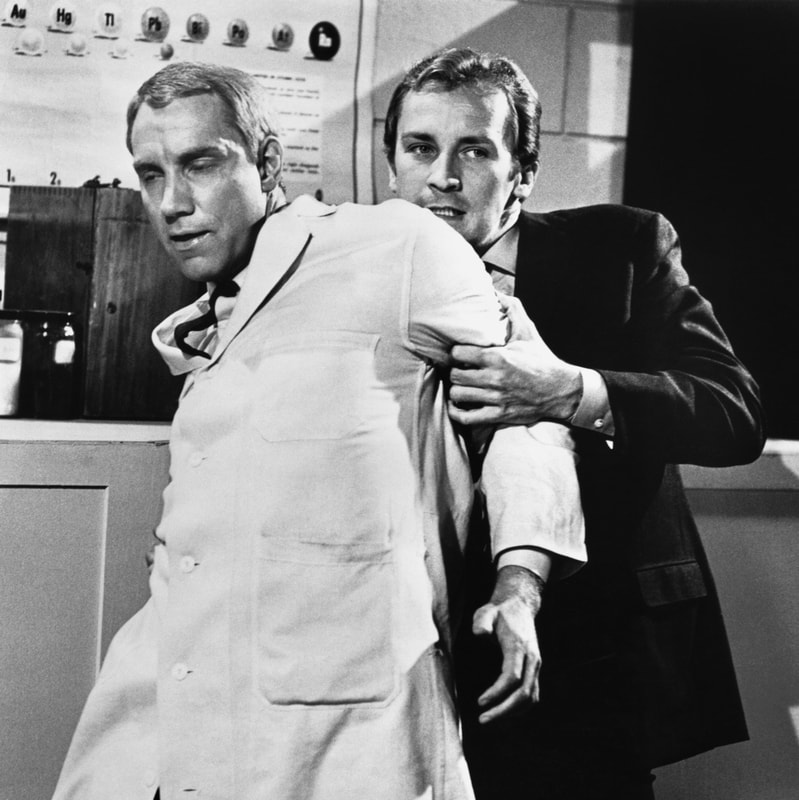

The Pit (The Invaders, 1968) with Roy Thinnes. The Mutation (The Invaders, 1967). The Mutation (The Invaders.1967). Beachhead (The Invaders.1967). Vincent’s quest to warn humanity of its imminent destruction brings him through a desolate American landscape. The Possessed (The Invaders, 1968) with William Smithers and Roy Thinnes.

|

Abridged from TV NOIR by Allen Glover. Published by Abrams Press. All rights reserved.