TV Noir |

A CLASSIC CYCLE

|

Hollywood Noir: Rise of the Telefilm

|

“Morning, noon and night the channels are cluttered with eye-wearying monstrosities called ‘films for tv’—half-hour aberrations that in story and acting would make an erstwhile Hollywood producer of ‘B’ pictures shake his head in dismay.”

✦ New York Times critic JACK GOULD, 1952 |

|

|

Live Drama may have provided a cultural cachet, an air of prestige, but it was the Hollywood-made telefilm, or filmed series, that supplied the hungry medium with its sustenance—its filler. While the studios argued internally about how, and for how much, they might get involved in television, the “eye-wearying monstrosities” that would finally unite and thoroughly transform both industries were already breeding along a stretch of Sunset Boulevard known as Poverty Row. Home to high-volume, low-cost stables like Monogram, Republic, and Eagle-Lion, and scores of fly-by-night hucksters, it was here that the telefilm was invented, with the “B” (or lower) crime melodrama being the preferred template.

As a speculative endeavor, the production of films for television held all the promise of a gold rush. Stanley Rubin was an out-of-work screenwriter with a pair of film noir “quickies,” Decoy (1946) and Violence (1947), to his name when he decided to go into television. Unwilling to remain idle during the studio slump of 1947–1948, he talked his co-writer on Violence, Lewis Lantz, into helping him adapt Guy de Maupassant’s short story “The Necklace” into a short film. Anthologies like the recently launched Kraft TV Theatre, Rubin surmised, were likely to become the mainstay of prime time—why not make one on celluloid? While neither screenwriter knew much about television, they had the foresight, along with their producer Marshall Grant (Moonrise, 1947), to pitch their series, known as Your Show Time, directly to a powerhouse sponsor, U.S. Tobacco, which in turn exercised its considerable muscle to find a berth for it in NBC’s Fall 1949 lineup. TV's first filmed series debuted just as the coaxial cable linking New York to Chicago brought the networks one time zone closer to becoming a fully national enterprise. With twelve stations in operation, and hundreds more awaiting licensing, it was amply clear that an alternative was needed to live programming. But where the appetite for ready-to-play material was bottomless, the means of settling the bill required some ironing out. Fireside Theatre (1949–1958) was the first to settle on a viable formula. To keep costs in line with what Procter & Gamble paid in commercial fees, it farmed production out to director-producers well versed in bare-bones practices, like John Reinhardt, who made The Guilty and For You I Die (both 1947) and Jack Bernhard, who put Rubin’s words into pictures in Decoy and Violence. Frank Wisbar, whose career traced back to Weimar cinema, was brought in to oversee the early seasons of Fireside; he was a “showrunner” before the term existed. With fellow émigrés Curt Siodmak and Arnold Phillips on his writing staff, he turned out one noir-inflected telefilm after another on an average budget of $17,000. Many, like “The Green Convertible” (1950), in which an unfaithful spouse is besieged with paranoid visions of a mysterious stalker, or “The Hot Spot” (1951), about a wife who shoots her gangster of a husband and escapes to the desert, deal with persecution and entrapment, themes familiar to those who fled Hitler. Others introduce an element of the absurd—an awareness of how quickly life can turn upside down. “Back to Zero” (1951) follows a girl chased by the police for reasons she’s unable to fathom. “Torture” (1951) features Vincent Price as a hitman hiding out in a labyrinthine tenement building from which there seems to be no exit. “Marked for Death” (1955), a thriller about a former POW hunting the Gestapo agent who tortured him, unwinds against morbid Day of the Dead festivities. Variety described it as a “stark drama of smoldering hatred and revenge that has the cutting edge of cold steel and grips like a vise.” TV Guide may have decried that Fireside Theatre “makes no attempt at artiness, profundity, or significance,” but by the end of its first season it was the second-most-watched program on the air (topped only by Mr. Television himself, Milton Berle). No other anthology of the 1950s, live or filmed, matched its popularity. The success of Fireside spurred many of the anthologies that began live, like Ford Theatre (1948–1957) and Schlitz Playhouse of Stars (1951–1958), to relocate westward, to where telefilms were made. By 1952, the production of films for television eclipsed the output of movies made for cinemas. Signs began appearing in film labs: “Unless otherwise specified, all film will be processed for TV.” From the Big Five (20th Century-Fox, MGM, Paramount, RkO, Warner Bros.) to the Little Three (Columbia, United Artists, Universal-International), the studios began renting out, or outright selling, their backlots to telefilm producers, or producing their own fare for television. The telefilm was here to stay, and Hollywood, nearly wiped out in the late 1940s, again became a boomtown. |

The Man Who Had Nothing to Lose (Bigelow Theatre, 1951) with Neville Brand. This was the first telefilm produced via Jerry Fairbanks’ Multi-Cam System, which sought to duplicate, on film, the three-camera video feed of live TV. Fairbanks failed to patent his invention; it became the standard for filmed sitcoms like I Love Lucy.

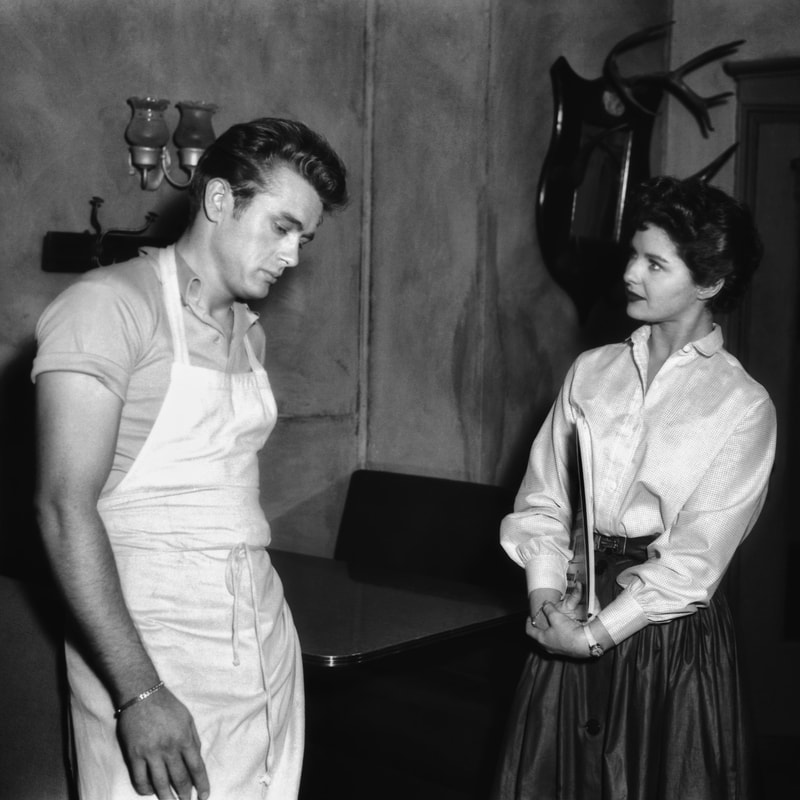

The Unlighted Road (Schlitz Playhouse of Stars, 1955) with James Dean and Patricia Hardy. Dean plays an ex-GI who accidentally kills a cop.

On the set of Pattern for Violence (Conflict, 1957) with Jack Lord and Charles Evans. Lord is a philandering banker accused of murdering his wife. Chased by the police to the flat of his mistress (the true killer), he’s taken his attorney hostage in hopes of negotiating an escape. Writer Howard Browne based the teleplay on his own 1947 pulp novel If You Have Tears.

|

|

|

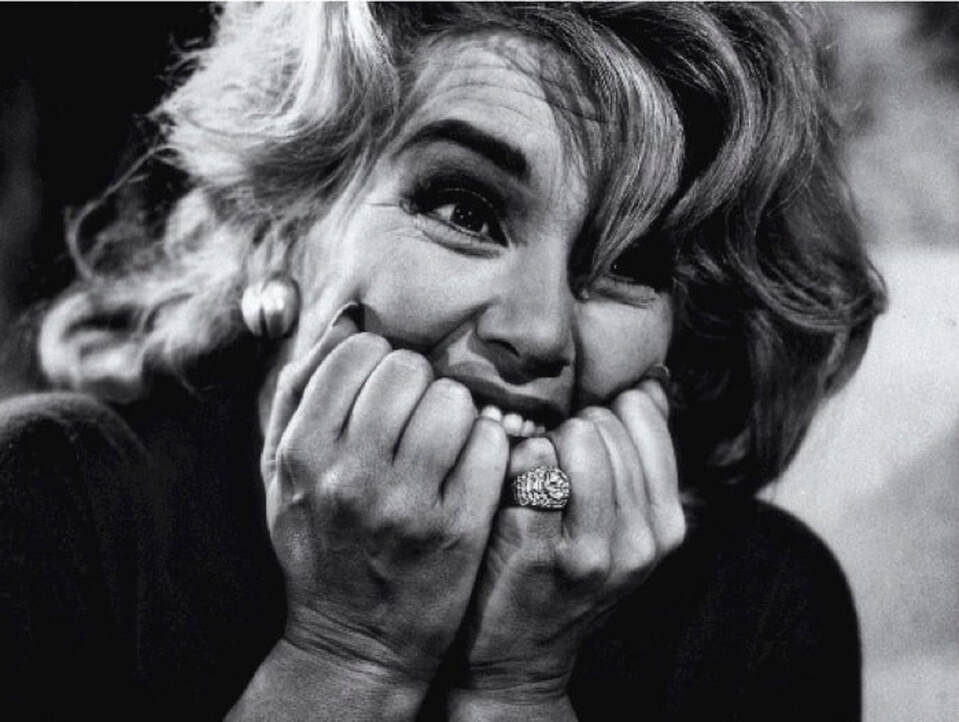

An Out for Oscar (Alfred Hitchcock Hour, 1963) with Linda Christian.

Series producer and story editor Joan Harrison drew freely from the well of pulp mysteries, such as this adaptation by David Goodis of a novel by Henry Kane. |

|

“It is paradoxical, of course, but the movie people hedge you in with all sorts of artistic restrictions; whereas in television I can quite literally get away with murder.“

✦ ALFRED HITCHCOCK |

|

The most prominent telefilm-maker of the 1950s was Alfred Hitchcock. In “Revenge” (1955), the opening segment of his eponymous anthology (1955–1965), he sets lovely, fragile Elsa (Vera Miles) afloat in a beach chair outside a mobile home while her husband, Carl (Ralph Meeker), trots off to his factory job. Carl returns home to find Elsa in a nearly catatonic state, the apparent victim of a sexual assault. “Uou think you’d recognize him if you saw him again?” Carl asks. “Oh, yes,“ Elsa promises.

Days go by. The police have no leads. Elsa remains listless and deeply traumatized, so Carl takes her for a drive into town.

Elsa suddenly points to a man on the sidewalk. “There he is— that’s him,” she says, definitively. Carl’s face darkens. He parks, collects a wrench from under the seat, and follows the man into a hotel. Hitchcock stages the killing obliquely, his camera peeking around a door frame as Carl’s creeping shadow does the business. Feeling vindicated, Carl replaces the soiled weapon beneath his seat and motors on. Husband and wife stare straight ahead, silent in their complicity. Blocks go by. Elsa perks up, jabbing her finger at another pedestrian. “There he is,” she insists. “That’s him.”

Hitchcock’s is a calamitous worldview in which neither prey nor predator is safe for long, a cynicism he typically renders with bursts of wicked drollness. Cue, for example, the doppelgänger who smugly inserts himself into the rigorously organized existence of a successful attorney in “The Case of Mr. Pelham” (1955). To his psychiatrist, Pelham (Tom Ewell) complains, “I have the feeling that he’s trying to move into my life, to crowd closer and closer to me so that one day he is where I was, standing in my shoes, my clothes, my life, and I—I am gone, vanished.”

Urged to break from his routine, Pelham purchases a garish tie, something the “real“ him would never wear. Having acted out of the ordinary, he’s now regarded as the impostor. “Why, why did this have to happen?” he cries out when the police arrive to evict him from his home. “No reason,” smirks the double, comfortably ensconced in Pelham’s robe and slippers. “It just did.”

Threats of immobility, alienation, and madness hang over the Hitchcockian heroes, inching them further toward catastrophe. “Four O’Clock” (1957), which Hitch directed from a story by Cornell Woolrich for another of his anthologies, Suspicion (1957–1958), casts E.G. Marshall as a watchmaker who hopes to kill his wife and her presumed lover with a homemade bomb. His plan goes awry when some burglars break in and tie him up in the basement, a few feet away from his ticking contraption. As his minutes wind down, he watches the world go by outside a small window—the gas man reading the meter, a neighborhood child chasing a bug, mundane events elevated to an altered state. Woolrich writes:

He couldn’t feel any more, terror or hope or anything else. A sort of numb- ness had set in, with a core of gleaming awareness remaining that was his mind. That would be all that the detonation would be able to blot out by the time it came. It was like having a tooth extracted with the aid of novocaine. There remained of him now only this single pulsing nerve of premonition; the tissue around it was frozen. So protracted foreknowledge of death was in itself its own anesthetic.

Hitchcock concludes with a canonical close-up of a face frozen in a death-mask stare, one of many ticks linking his television work to his film work. By his own admission, the telefilms he directed were “purer and with fewer concessions” than the features he made. “It is paradoxical, of course,“ he said, “but the movie people hedge you in with all sorts of artistic restrictions; whereas in television I can quite literally get away with murder.“

With “One More Mile to Go“ (1957), Hitch puts us directly in the mind frame of a murderer. He opens with a jerky handheld shot of a rural home and the sounds of a man and a woman in vicious disagreement. The effect is voyeuristic, as if we’ve pulled over on a dark highway and crept through some trees to spy on the lives of the country folk. A jump cut brings us to the window just in time to see the husband swing a fire iron at his wife; the next edit takes us inside as he steps back to survey, with uneasy satisfaction, her crumpled corpse. For the rest of “One More Mile to Go,” as Sam Jacoby (David Wayne), cleans up his tracks, neatly wraps the body in a tarp, and drives off to dispose of it, we’re given a step-by-step rehearsal for the sequence of Norman Bates tidying up “mother’s” dispatching of Marion Crane in Psycho (1960).

There are other moments of overlap as well, like the interrogation by a brutish, meddlesome cop which both Crane and Jacoby are made to endure. Hitchcock made Psycho cheaply and quickly, forsaking his usual crew for the one from Alfred Hitchcock Presents. His little black-and-white crowd pleaser, with its lurid subject matter, ironic sensibility, and stark visuals (framed at a television-like 1.37:1 aspect ratio), asserts itself as a stretch-out of the half-hour playlets he presented each week on television—a venue he seriously considered during its troubled journey toward theatrical release. His television earnings, after all, had paid for it: no studio would bankroll the film.

Psycho confused the distinction between “A” and “B” product, high and low art, spectacle and small-scale, in much the same way the first wave of telefilm series encouraged viewers to accept filmed television as but a differently delivered form of moving-image storytelling. While an admirer of live television—see, for instance, his Rope (1948), with its loping track shots—Hitchcock unwittingly became the lead pallbearer at its funeral. His very involvement in telefilms, the pedigree he lent the form, the polish he insisted upon, provided the final, necessary push toward a level of respectability and mass acceptance. The dramatic television we enjoy today owes its lineage to the “eye-wearying monstrosities“ once known as telefilms.

Days go by. The police have no leads. Elsa remains listless and deeply traumatized, so Carl takes her for a drive into town.

Elsa suddenly points to a man on the sidewalk. “There he is— that’s him,” she says, definitively. Carl’s face darkens. He parks, collects a wrench from under the seat, and follows the man into a hotel. Hitchcock stages the killing obliquely, his camera peeking around a door frame as Carl’s creeping shadow does the business. Feeling vindicated, Carl replaces the soiled weapon beneath his seat and motors on. Husband and wife stare straight ahead, silent in their complicity. Blocks go by. Elsa perks up, jabbing her finger at another pedestrian. “There he is,” she insists. “That’s him.”

Hitchcock’s is a calamitous worldview in which neither prey nor predator is safe for long, a cynicism he typically renders with bursts of wicked drollness. Cue, for example, the doppelgänger who smugly inserts himself into the rigorously organized existence of a successful attorney in “The Case of Mr. Pelham” (1955). To his psychiatrist, Pelham (Tom Ewell) complains, “I have the feeling that he’s trying to move into my life, to crowd closer and closer to me so that one day he is where I was, standing in my shoes, my clothes, my life, and I—I am gone, vanished.”

Urged to break from his routine, Pelham purchases a garish tie, something the “real“ him would never wear. Having acted out of the ordinary, he’s now regarded as the impostor. “Why, why did this have to happen?” he cries out when the police arrive to evict him from his home. “No reason,” smirks the double, comfortably ensconced in Pelham’s robe and slippers. “It just did.”

Threats of immobility, alienation, and madness hang over the Hitchcockian heroes, inching them further toward catastrophe. “Four O’Clock” (1957), which Hitch directed from a story by Cornell Woolrich for another of his anthologies, Suspicion (1957–1958), casts E.G. Marshall as a watchmaker who hopes to kill his wife and her presumed lover with a homemade bomb. His plan goes awry when some burglars break in and tie him up in the basement, a few feet away from his ticking contraption. As his minutes wind down, he watches the world go by outside a small window—the gas man reading the meter, a neighborhood child chasing a bug, mundane events elevated to an altered state. Woolrich writes:

He couldn’t feel any more, terror or hope or anything else. A sort of numb- ness had set in, with a core of gleaming awareness remaining that was his mind. That would be all that the detonation would be able to blot out by the time it came. It was like having a tooth extracted with the aid of novocaine. There remained of him now only this single pulsing nerve of premonition; the tissue around it was frozen. So protracted foreknowledge of death was in itself its own anesthetic.

Hitchcock concludes with a canonical close-up of a face frozen in a death-mask stare, one of many ticks linking his television work to his film work. By his own admission, the telefilms he directed were “purer and with fewer concessions” than the features he made. “It is paradoxical, of course,“ he said, “but the movie people hedge you in with all sorts of artistic restrictions; whereas in television I can quite literally get away with murder.“

With “One More Mile to Go“ (1957), Hitch puts us directly in the mind frame of a murderer. He opens with a jerky handheld shot of a rural home and the sounds of a man and a woman in vicious disagreement. The effect is voyeuristic, as if we’ve pulled over on a dark highway and crept through some trees to spy on the lives of the country folk. A jump cut brings us to the window just in time to see the husband swing a fire iron at his wife; the next edit takes us inside as he steps back to survey, with uneasy satisfaction, her crumpled corpse. For the rest of “One More Mile to Go,” as Sam Jacoby (David Wayne), cleans up his tracks, neatly wraps the body in a tarp, and drives off to dispose of it, we’re given a step-by-step rehearsal for the sequence of Norman Bates tidying up “mother’s” dispatching of Marion Crane in Psycho (1960).

There are other moments of overlap as well, like the interrogation by a brutish, meddlesome cop which both Crane and Jacoby are made to endure. Hitchcock made Psycho cheaply and quickly, forsaking his usual crew for the one from Alfred Hitchcock Presents. His little black-and-white crowd pleaser, with its lurid subject matter, ironic sensibility, and stark visuals (framed at a television-like 1.37:1 aspect ratio), asserts itself as a stretch-out of the half-hour playlets he presented each week on television—a venue he seriously considered during its troubled journey toward theatrical release. His television earnings, after all, had paid for it: no studio would bankroll the film.

Psycho confused the distinction between “A” and “B” product, high and low art, spectacle and small-scale, in much the same way the first wave of telefilm series encouraged viewers to accept filmed television as but a differently delivered form of moving-image storytelling. While an admirer of live television—see, for instance, his Rope (1948), with its loping track shots—Hitchcock unwittingly became the lead pallbearer at its funeral. His very involvement in telefilms, the pedigree he lent the form, the polish he insisted upon, provided the final, necessary push toward a level of respectability and mass acceptance. The dramatic television we enjoy today owes its lineage to the “eye-wearying monstrosities“ once known as telefilms.

Side by Side: One for the Road (Alfred Hitchcock Presents, 1957) >< Psycho (1960).

One More Mile to Go, from a story by Emily Duff, blueprints two of the key set-pieces of Hitchcock’s later Psycho: the suspenseful driving sequence that brings Marion Crane to the Bates Motel, and the methodical cleaning-up set-piece enacted by Norman Bates after “Mother” nudges round his business.

Abridged from TV Noir by Allen Glover. Published by Abrams Press. All rights reserved.