TV Noir |

LIVE NOIR

|

The Black Angel and Other Lost Noir

“Oh, it was so dark along this street. Just that hooded, half-dimmed light on the other side, too far behind me to do any good any more.” ✦ THE BLACK ANGEL by CORNELL WOOLRICH

|

The Black Angel, fourth in Cornell Woolrich’s “black series,” is the basis for television’s first serialized drama—a cornerstone of TV noir. Like many of Woolrich’s stories, it is both a clock-race mystery and a chronicle of a heroine’s passage through a heretofore unrevealed world. Alberta Murray, played by Mary Patton, is twenty-two, a content newlywed until the day her husband Kirk stops calling her by her pet name, “Angel Face.” Fearing the worst, Alberta tracks down the “other woman,” Mia Mercer, only to find that she’s been murdered. When Kirk is convicted of the crime and sentenced to death, Alberta sets out to prove his innocence. Her clues in this endeavor, surreptitiously lifted from the crime scene, are a matchbook monogrammed “M” and the four corresponding “M” names (excepting her husband’s) in Mia’s little black book: Marty, Mordaunt, Mason, and Mckee. Through masquerade, deceit, and manipulation, Alberta insinuates herself into the lives of each sus pect until she finds the real killer.

Unfolding episodically, in self-contained vignettes that add up to a larger whole, Woolrich’s novel, published in 1943, is a marvel of structured suspense. Each of the four men, Alberta discovers, had good reason to off Mia. In attaching herself to them, Alberta in effect replaces her deceased rival, of whom a policeman warns, “you’re not her type; you wouldn’t know how to handle these people.” Discarding the advice (as in most Woolrich stories, the police are dispensable until needed), Alberta sets off through “a world of jungle violence and of darkness, of strange hidden deeds in strange hidden places, of sharp-clawed treachery and fanged gratitude.” Having begun the story as a sheltered innocent, she concludes her quest for marital restitution thoroughly despoiled and with considerable carnage in her wake. Infected by the sordid, corruptive world in which her husband became entangled, Alberta merely spreads things around. Presented over four Sundays in early 1945 by NBC’s flagship station, WNBT, The Black Angel marked the reactivation of the network’s “live talent” unit after a war-imposed hiatus. In seizing upon Woolrich’s book, as of yet undiscovered by Hollywood, the network sought to align its ambitious slate of forthcoming dramatic productions with a type of dark melodrama already proved popular on radio, and quickly gaining momentum in cinema. Ernest Colling, the NBC writer-director tasked with bringing the property to television, described it as “a natural for television production inasmuch as it is a psychological drama and therefore perfectly adaptable to the new medium.” Colling’s teleplay, unlike Universal’s subsequent film version (Black Angel, 1946), is near-faithful to its source, with the novel’s four central chapters comprising the four episodes of the television serial: “Heartbreak,” “Dr. Death,” “Play- boy,” and “The Last Name.” |

On the set of The Black Angel (1945) with Mary Patton.

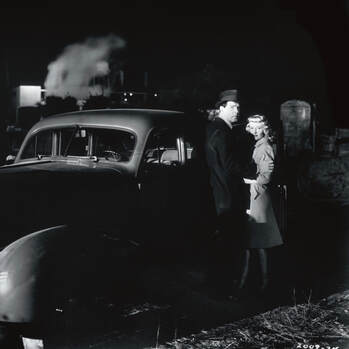

On the set of The Black Angel (1945) with Paul Conrad and Mary Patton.

|

The Black Angel is unique for Woolrich in that it’s told from the first-person perspective of his heroine, the effect of which, as his biographer, Francis M. Nevins, Jr., has pointed out, is that we are “trapped inside the narrator’s warped soul, knowing everything she knows, feeling everything she feels, her terror and desperation and murderous obsession growing like a cancer within.” “I was alone,” Alberta admits, early in the novel, “a lost, frightened thing straying around, my whole world crumbling away all around me like the shell of an egg.” We are also privy to the erosion of Alberta’s innocence, her growing awareness of the world as no longer a place of light but of pitiless darkness. “This was it now,” she relays as she scours the Bowery for Marty Blair. “The lowest depths of all, this side the grave. There was nothing beyond this, nothing further. Nothing came after it—only death, the river. These were not human beings any more. These were shadows.” Having penetrated the noir world, Alberta continues on, undeterred in her determination “to make contact and fasten myself onto them.”

Colling, when adapting The Black Angel for television, retained the singularity of this perspective by supplying Alberta with a voiceover, most of it taken verbatim from Woolrich’s text. While subjective narration was common in radio drama of the 1930s and early 1940s (e.g. Lights Out), it was all but unheard of in television, and still relatively new to cinema, with Double Indemnity (1944) and Murder, My Sweet (1944) being notable exceptions. In these films noirs, the voiceovers of Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray) and Philip Marlowe (Dick Powell) operate in tandem with a confessional framing structure wherein the bulk of the story plays out in flashback. Neff, for instance, begins his narration of Double Indemnity by wondering, “How could I have known that murder would smell like honeysuckle?”—situating his tale as one of posthumous appraisal. Alberta’s voiceover, in contrast, is correlated to a bewildering succession of events unfolding in the narrative present, an approach perfectly suited to the immediacy of live television.

The Black Angel aired a few years before kinescoping, the process of filming (and thus preserving) a live broadcast from the studio monitor, was put into practice. Aside from a handful of production stills, and Colling’s personal script, it survives only in the form of Alberta’s voiceover, as cut to vinyl by Mary Patton prior to each broadcast and played back, with what must have required impeccable coordination, in concert with the spoken dialogue of the live performance. (These recordings, uncovered among the uncatalogued holdings of the Library of Congress in the course of preparing this book, are the earliest artifacts of a made-for-television noir.) Narratively, there’s little need for Alberta’s near- continuous voiceover—the story could just as well have been told without it, through perhaps not as interestingly. And so it becomes a stylistic choice, a means of urging the viewer to occupy the same anxious, paranoid state from which Alberta herself cannot escape.

Colling, when adapting The Black Angel for television, retained the singularity of this perspective by supplying Alberta with a voiceover, most of it taken verbatim from Woolrich’s text. While subjective narration was common in radio drama of the 1930s and early 1940s (e.g. Lights Out), it was all but unheard of in television, and still relatively new to cinema, with Double Indemnity (1944) and Murder, My Sweet (1944) being notable exceptions. In these films noirs, the voiceovers of Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray) and Philip Marlowe (Dick Powell) operate in tandem with a confessional framing structure wherein the bulk of the story plays out in flashback. Neff, for instance, begins his narration of Double Indemnity by wondering, “How could I have known that murder would smell like honeysuckle?”—situating his tale as one of posthumous appraisal. Alberta’s voiceover, in contrast, is correlated to a bewildering succession of events unfolding in the narrative present, an approach perfectly suited to the immediacy of live television.

The Black Angel aired a few years before kinescoping, the process of filming (and thus preserving) a live broadcast from the studio monitor, was put into practice. Aside from a handful of production stills, and Colling’s personal script, it survives only in the form of Alberta’s voiceover, as cut to vinyl by Mary Patton prior to each broadcast and played back, with what must have required impeccable coordination, in concert with the spoken dialogue of the live performance. (These recordings, uncovered among the uncatalogued holdings of the Library of Congress in the course of preparing this book, are the earliest artifacts of a made-for-television noir.) Narratively, there’s little need for Alberta’s near- continuous voiceover—the story could just as well have been told without it, through perhaps not as interestingly. And so it becomes a stylistic choice, a means of urging the viewer to occupy the same anxious, paranoid state from which Alberta herself cannot escape.

“I traveled blindly along the tunnel-like basement bore like someone pacing in a dream. A dream whose foreknown outcome is doom, yet which must unfold itself without reprieve to its appointed climax.“ ✦ THE BLACK ANGEL

|

As NBC’s most ambitious offering since it began service in 1937, The Black Angel set the standard for the “live talent” presentations to follow. Indeed, the network used the occasion to measure, for the first time, public response to a dramatic production. Along with mailing surveys out to the five thousand or so television-equipped households in New York City circa January 1945, it concluded each episode with an open invitation for viewers to write in with their comments. Thereafter, dark tales of murder and mystery proliferated. Many of them, including Woolrich’s own The Black Alibi, which NBC presented over two nights in 1946, followed the open-ended whodunit scenario of The Black Angel, a form thought to be instrumental in retaining viewership. “We won back the same audience every Sunday night, plus new ones,” explained Mary Patton. “The tele-audience had to wait weeks to find the answer and the suspense was too much for them!” (Yes, even in the 1940s, Sunday was the night for prestige television.) For the most part, however, the noir-infused one-offs aired by NBC and, competitively, by CBS and DuMont in the second half of the 1940s, as the networks sussed out what types of programming audiences might most want to see, were of the “red meat” variety popularized by James M. Cain. That the sensibility of these productions was in tune with what Cain liked to describe as “blood melodrama” is best summarized in Billboard’s sighing complaint: “NBC tonight presented another in its studies of husband-killing wives.”

Stories like these, with their undercurrents of marital discord, murderous fixation, and corrosive guilt, point toward the influence of Cain’s Double Indemnity, which finally made it to cinemas in 1944 after a near-decade of Hays Office suppression. But it also highlights the increasing acceptability of such themes as suitable for television. Given that the purpose of presentations like The Black Angel was to popularize television for the postwar masses, the dark mystery-melodrama clearly served as an integral part of network strategy from the beginning of commercial television. “Crime plays are now enjoying unprecedented popularity on stage, screen, and on the air,” Televiser reported in 1946, citing the trend toward stories with “psychological and psychopathological complications” as especially appealing. “Through its continually moving spatial cameras, television is able to show in defocused shots, close-ups, angle shots, and surprising dollies how the world appears to the neurotic, the criminal and the insane. Unlike the theatre it can create a subjective reality and effect subconscious identification of the viewer with the criminal who invades his living room.” |

Double Indemnity (film, 1944)

with Barbara Stanwyck and Fred MacMurray. |

Abridged from TV Noir by Allen Glover. Published by Abrams Press. All rights reserved.