TV Noir |

A CLASSIC CYCLE

|

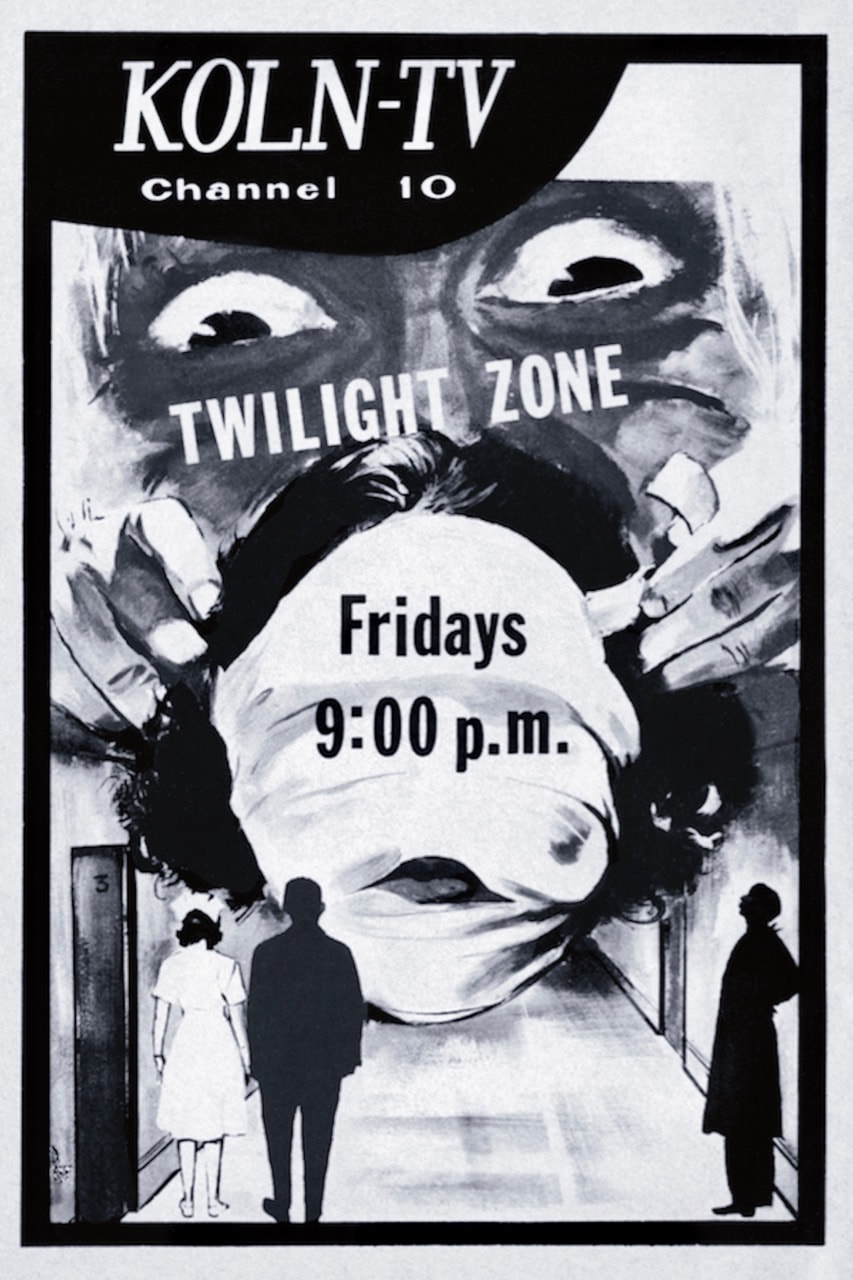

The Twilight Zone |

CBS 1959 – 1964

|

|

“As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams he found himself transformed in his bed into a gigantic insect-like creature.”

✦ FRANZ KAFKA, The Metamorphosis |

|

|

More than half a century on, the very title of The Twilight Zone remains in the public lexicon as a signifier of eerie ambiguity. As with much post- war film noir, particularly those strains developed beneath the shadow of the Bomb, it posits a universe in which the chasm between security and annihilation looms open-mouthed. Dispatched by fate to “a fifth dimension beyond that which is known to man”—as Rod Serling, who created the show, and narrates each of its episodes, explains over the main titles—its characters all find themselves neck-deep in a noir nightmare that’s been turned inside out and stretched to its full otherworldly potential.

Serling arrived at this speculative realm by way of a prolific decade as one of the leading dramatists of the live anthologies. When it was announced that he was doing a telefilm series, and a genre-based one at that, many assumed, as Mike Wallace indelicately put it during an on-air interview, that he’d “given up writing anything important for television.” Far from it. Through metaphor, irony, and paradox, the socially conscious themes and stark naturalism with which he made his name are reshaped within the complex and illusory continuum of a fever dream: Serling spins these tales with a surrealist’s knack for exposing truths in unexpected places. Each Twilight Zone tale begins deceptively, grounded in the recognizable, before shoving its hapless protagonist beyond the lip of the uncanny. It’s an abyss not at all well marked. Those who tumble down it find themselves in a dark and nebulous dreamscape in which life’s reliable features have been compromised, perhaps irretrievably; Serling liked to describe it as “the shadowy area of the almost-but-not-quite.” In lieu of a sturdy foothold, doubt, self- division, and anxiety creep in: the passenger becomes a neurotic mess, lonely and dispossessed, and in perpetual terror of the next catastrophe. This is the conditional state of being in the Zone, which is as much a destination as it is a designation—a barometer for the collective psyche in the Age of Duck-and-Cover. The threat of apocalypse saturates The Twilight Zone. even in those episodes not directly concerned with nuclear cataclysm, there persists an air of premonition, a fear of the instant when the lights are permanently put out. Time and again, there’s the nagging sense that this is not the way things are meant to be. How did the forces of menace gain control? At what point did the future become so formless and inscrutable? Faced with prevailing darkness, powerless to hinder it, the populace becomes insecure and self-absorbed. Confusion and fear lurch into violence and hysteria. A power outage gives rise to a frenzied mob intent on rooting out the “others” in their midst (“The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street”). An unidentified flying object compels friends and neighbors to tear at one another in a desperate rush to find a place to hide (“The Shelter”). In these and other parables, the inexorable march toward finality has already begun. Douglas Heyes, who directed “Eye of the Beholder,”

|

Where Is Everybody? (1959) with Earl Holliman.

On the set of The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street (1960)

with Jack Weston, Burt Metcalfe, Jason Johnson, and Amzie Strickland. Advert for Eye of the Beholder (The Twilight Zone, 1960).

|

Excerpted and adapted from TV NOIR by Allen Glover. Published by Abrams Press. All rights reserved.