TV Noir |

NEO NOIR

|

Danger Man |

CBS 1961 – 1966

|

|

The Prisoner

|

CBS 1968

|

|

“Every government has its secret service branch. America, its CIA. France, Deuxième Bureau. England, MI5. NATO also has its own. A messy job? Well, that’s when they usually call on me, or someone like me. Oh, yes, my name is Drake, John Drake.”

✦ OPENING NARRATION, Danger Man |

|

|

Having spelled out his mandate within the alphabetic runes of the spy trade, John Drake (Patrick McGoohan), an international specialist at “messy jobs,” saunters from a modernist glass structure, tosses a smart-looking jacket in the back of an even smarter sports car, and speeds away. A swelling jazz theme punctuates the title card. Were it not for the promise of global adventure, this could well be Peter Gunn or Staccato. Danger Man debuted in the Uk in 1960, on the cusp of the secret agent craze that would grip the decade; the first James Bond film, Dr. No, was still two years away. The series’ immediate antecedent is the literary Bond, as introduced by Ian Fleming with Casino Royale (1953), a work whose pulp tensions and fatalistic plotting owe much to the noir ethos. Looking back further still, Danger Man draws upon the rich legacy of the cloak-and-dagger tale.

The British spy thriller, like its American counterpart, the hardboiled detective story, deals in quests, its heroes setting forth through a landscape of treachery. Raymond Chandler liked to de- scribe the milieu as “a world run by gangsters.” Joseph Conrad, in The Secret Agent (1907), his great novel of sabotage and intrigue, characterizes it as “this earth of evil.” Conrad’s prescient vision of the spiritual disfigurement and senseless calamity that would mark the twentieth century effectively invented the modern espionage story. Through two world wars and up to the brink of a third, his prototype gained picaresque structure in John Buchan’s The Thirty-Nine Steps (1915); autobiographical legitimacy in Somerset Maugham’s Ashenden (1922); and a measure of psychological realism in the works of Eric Ambler (Epitaph for a Spy, 1937) and Graham Greene (The Confidential Agent, 1939). All of these writers, but especially Ambler and Greene, were important to film noir—which, by the advent of the Cold War, occupied much the same thematic and psychic terrain as the spy genre. In this postwar climate, Fleming’s decadent rogue rose to popularity in print, followed in due order by the determinedly more understated Drake of television. Danger Man was created by writer-producer Ralph Smart. His espionage-themed series The Invisible Man (1957–1958), a reworking of the H.G. Wells classic, was the first contemporarily set British program to crack the lucrative American market. Commissioned by ITC boss Lew Grade to devise something similar, Smart responded with a treatment, reportedly fleshed out with input from Fleming, about a well-traveled man of intrigue whose assignments put him on the forefront of the Cold War. There were some early discussions about bringing Bond himself to television, but as legal matters surrounding the novels prevented that, Smart enlisted Ian Stuart Black and Brian Clemens, his writers on The Invisible Man, to further develop the character, at that stage known as “Lone Wolf.” The result was John Drake, an Irish-American (like McGoohan) security specialist at the beck and call of NATO—a hero of transatlantic appeal. Touching down someplace exotic—Lisbon one week, Hong kong the next, all impeccably conveyed with second-unit background plates—Drake hits the ground at a blistering pace: there are chases, spectacular bouts of action, double- and triple-dealings, masquerades and charades. Crisis resolved, he beats a hasty exit via the nearest train, plane, or boat. In the U.S., CBS aired the half-hour Danger Mans in the summer of 1961, just as the Berlin Wall was going up; the entire series remained in worldwide syndication until 1964, when it was reactivated in hour-long form. In this incarnation, Drake works mostly for M9, a make-believe wing of Her Majesty’s Secret Service. even then, his assignments seem to come down from someplace else. Danger Man’s high-gloss production values (it was the most expensive British program of its day) do little to disguise an overriding tone of pessimism and bleakness, an impression fostered, visually, by its stark monochromatic photography. In contrast to the fantastical airs of contemporaneous fare like The Man From U.N.C.L.E. (1964–1968), Get Smart (1965–1970), or Mission: Impossible (1966–1973), Danger Man favors a world-on-the-brink-of-nuclear-winter realism, which perhaps explains the alterations made to the series for its reintroduction to U.S. audiences as Secret Agent. Beyond the re-titling, CBS scrapped the original's enigmatic title sequence, with its interplay of positive-negative imagery, and replaced Edwin Astley’s harpsichord theme with the surf rock–inspired “Secret Agent Man,” sung by Johnny Rivers. Having never seen Danger Man, lyricists Steve Barri and P. F. Sloan looked to the 007 franchise for inspiration, yielding a song of dubious compatibility to the low-key work at hand. yet one stanza stands out, for it curiously foreshadows the enumeration to be foisted upon Number Six in The Prisoner, McGoohan’s follow-up to Danger Man: “They’ve given you a number / And taken away your name.” The expendability of an agent, a salient theme, emerges as a central question of The Prisoner. As Danger Man progresses, Drake is steadily pressed with ennui. He feels the British empire crumbling around him; he has no one to trust and nothing concrete to believe in, yet he strives mightily to retain his scruples. The sense that he’s staked his life, and the lives of others, on a geopolitical chess match of futile aim builds until, finally, in The Prisoner, Drake—or rather his avatar, the anonymous Number Six—calls it quits. It’s well known that McGoohan went to his grave insisting that The Prisoner was not a sequel to Danger Man. While this may be the “official” case, there’s no denying the link between Drake’s disillusionment and petulance and Number Six’s defiance and anti-authoritarianism. |

Fair Exchange (Danger Man, 1964).

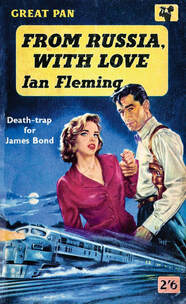

FROM LEFT: From Russia With Love (Ian Fleming, Pan, 1957)

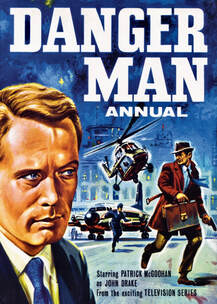

and Danger Man Annual (World Distributors, 1965). On the set of Free for All (The Prisoner, 1967) with Patrick McGoohan.

Filming took place in Portmeiroin, Wales, a location also used in Danger Man. |

Abridged from TV NOIR by Allen Glover. Published by Abrams Press. All rights reserved.