TV Noir |

Introduction

|

Lights Out in the Wasteland

It is a not a fragrant world, but it is the world you live in, and certain writers with tough minds and a cool spirit of detachment can make very interesting and even amusing patterns out of it. ✦ RAYMOND CHANDLER

|

Ever since film noir entered Anglo-American criticism in the late 1960s, the debate has raged as to whether it constitutes a genre, a movement, an attitude, or a style. Alfred Appel, writing in Film Comment in 1974, suggested that “what unites the seemingly disparate kinds of films noirs [is] their black vision of despair, loneliness, and dread—a vision that touches an audience most intimately because it assures them that their suppressed impulses and fears are shared human responses.” Pushed into darkness, made aware of the world as a place of danger and death, the disoriented characters of noir seek a return to the light—a truth, a reckoning, some form of absolution.

Among the earliest writers to describe his own work as “noir” (well before it had a fancy name) was Cornell Woolrich, beginning with The Bride Wore Black (1940), first in his “black series.” Woolrich’s is a frightfully unstable universe in which the membrane between light and dark, safety and pitfall, is bound to burst at any time. Dashiell Hammett, in The Maltese Falcon (1930), hints at such volatility with his story-within-a-story of the falling beam that awakens the sleepwalking Flitcraft, who up till then had foolishly believed that life “was a clean orderly sane responsible affair,” to the fact “that life was fundamentally none of those things.” And Franz Kafka, earlier in the century, wrote of the sudden irreversible horrors that can befall the unsuspecting. But Woolrich shaped an entire oeuvre around a singularly dark and pessimistic worldview in which human existence is dominated by malevolent, impersonal forces. Immensely prolific, he provided the stories for more works of radio, film, and television noir than any other writer of the pulp school. His impact on noir, whether acknowledged or uncredited (his plots and tropes are regularly mimicked), is monumental, and his delineation of the asphalt nightscape endures. |

Altered Carbon (2017) with Joel Kinnaman.

|

Though the appeal of film noir is quite direct, its essence remains nebulous, particularly when one widens the parameters of its generally agreed-upon time-frame and takes into account the antecedents and the stragglers, as well as its transgeneric infiltration. The artistic and sociological developments that gradually fused into the so-called classic cycle of film noir (1940–1958) also coincided with the emergence of television as a mass medium—a vast arena for the telling of stories. yet the reams of discourse on film noir have, for the most part, sidestepped any serious discussion of a noir ethos on television. Those works that do address it tend to position television noir as having evolved in the wake of, rather than concurrently with, film noir—a chase-the-tail approach perhaps shaped by the dearth of surviving programs from television’s early live phase. The hundreds of live dramas staged on television during the 1940s and 1950s (the first full decades of commercial broadcasting) represent a key dimension of mid-century noir. Alongside adaptations of novels by Woolrich, Chandler, Hammett, David Goodis, W. R. Burnett, Dorothy B. Hughes, and others of the literary noir tradition, a generation of teleplay writers supplied the medium with original tales of American alienation and discontent reflective of an overall darkened cultural mood.

Another factor compounding the classification of television noir is that from the early 1950s, as it became apparent that the networks’ model of a “living theatre of the air” was unsustainable, television increasingly became a conduit for filmed series, or telefilms, produced in Hollywood. A substantial portion of the programming within the mosaic of TV noir is but a parallel strain of filmed noir, produced and canned in much the same way as theatrical film noir. The noir telefilm has its origins in the “B” films, or lower-bill programmers, churned out by the studios’ specialty divisions or along Poverty Row—wellsprings of what we now label film noir. (Comparatively few classic-cycle titles could be considered “A” productions.) As “B” product began to fall out of favor with exhibitors, its writers, directors, actors, and cinematographers flooded the emerging telefilm market. By 1952, when Variety declared crime drama to be “the most attractive form of television presentations from the point of view of sponsors,” more than half of the two dozen such series on the air were made in Hollywood, in many cases by the same filmmakers who had filled cinemas with film noir.

In this regard, the most glaring difference between film and television noir is the matter of delivery: cinema versus living room. Because each draws upon the same dramaturgical principles and visual vocabulary, one can discuss an episode of Dragnet (1951–1958) with the same approach to narrative, style, and tone with which one might appraise a “B” noir like He Walked by Night (1948). On the other hand, episodic television offers something the movies do not: the time and space to extend a noir premise into countless variations of the same dark tale, told and re-told in different ways.

Another factor compounding the classification of television noir is that from the early 1950s, as it became apparent that the networks’ model of a “living theatre of the air” was unsustainable, television increasingly became a conduit for filmed series, or telefilms, produced in Hollywood. A substantial portion of the programming within the mosaic of TV noir is but a parallel strain of filmed noir, produced and canned in much the same way as theatrical film noir. The noir telefilm has its origins in the “B” films, or lower-bill programmers, churned out by the studios’ specialty divisions or along Poverty Row—wellsprings of what we now label film noir. (Comparatively few classic-cycle titles could be considered “A” productions.) As “B” product began to fall out of favor with exhibitors, its writers, directors, actors, and cinematographers flooded the emerging telefilm market. By 1952, when Variety declared crime drama to be “the most attractive form of television presentations from the point of view of sponsors,” more than half of the two dozen such series on the air were made in Hollywood, in many cases by the same filmmakers who had filled cinemas with film noir.

In this regard, the most glaring difference between film and television noir is the matter of delivery: cinema versus living room. Because each draws upon the same dramaturgical principles and visual vocabulary, one can discuss an episode of Dragnet (1951–1958) with the same approach to narrative, style, and tone with which one might appraise a “B” noir like He Walked by Night (1948). On the other hand, episodic television offers something the movies do not: the time and space to extend a noir premise into countless variations of the same dark tale, told and re-told in different ways.

“Whodunits are a natural for surefire audience response as indicated by radio’s Hooper ratings and it doesn’t take a swami to foresee a rash of them breaking out on the videolanes.“ ✦ VARIETY, 1946

|

Following an aborted prewar start, television relaunched itself in late 1944. NBC set the standard with an ambitious four-part adaptation of Woolrich’s The Black Angel (1945), a property selected as much for its dark, psychological tone as for the fact that its author was an exceptionally reliable fountain of stories for radio noir anthologies like Suspense (1942–1962) and The Molle Mystery Theatre (1943–1954). Early television molded itself on the programming formats that were most popular with a nation of radio listeners, in particular the mystery-suspense anthology, but also the police procedural, the private-eye show, the spy series, and the newspaper drama. Contingent to these generic forms, TV also took from radio its emphasis on mood and characterization, and, significantly, its reductive simplification of plot into easily ingestible (and commercially interruptible) segments. Radio, arriving on the scene around the same time as the talkies, is rarely mentioned among the host of factors that fostered a public demand for darker stories, yet its cultural pervasiveness was at least equal to that of the cinema for most of the 1930s and 1940s.

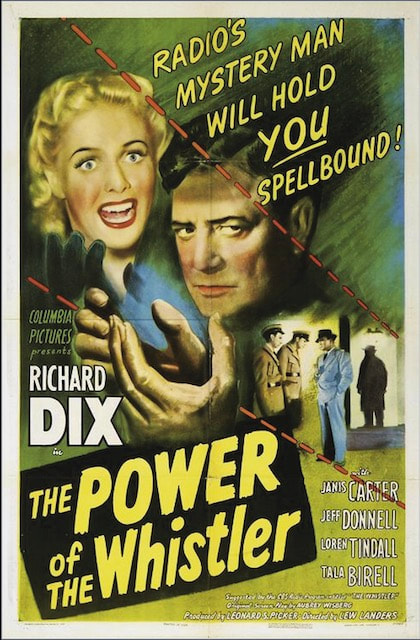

As a conduit for storytelling, radio had the distinct advantage of being a home appliance, inducing, as Aldous Huxley tartly put it, “a craving for daily or even hourly emotional enemas,” an addictive quality later transferred to another household staple, the television set. Radio not only introduced a formulaic approach to narrative construction—timed to the split second to fill a quarter-or half-hour slot—but it filled America’s airwaves with a veritable spectrum of lurid crime, psychoneurotic behavior, and horrific undoing. The disturbing and unseemly ambience of radio noir not only prepared American audiences for the noir fictions of film and television, but also inspired the techniques deployed to dramatize a noir story once it left the page. Billy Wilder, for one, admitted that in adapting Double Indemnity for the screen, he based the framing device of a voiceover—the dying confession Walter Neff narrates into a dictaphone—on the radio tactic of the interior monologue. The images conjured by radio noir are just as much the product of the listener’s imagination as they are of the verbally doled-out exposition: “Out of the dark of the night, from the shadows of the senses, comes this—the fantasy of fear,” intones Peter Lorre as the host of Nightmare, one of many noir-infused anthologies. Indeed, the most memorable radio noir hinges on a persuasive evocation of the unknown—darkness, nightfall, shadows, the void. These are stories of inner dread, the dark night of the soul, a milieu made clear in the catchphrases of the Shadow and the Whistler, two of the more popular radio heroes of the era. The Shadow’s eerie come-on, “Who knows what evil lurks in the minds of men? The Shadow knows!” is echoed by that of the Whistler: “I am the Whistler and I know many things, for I walk by night. I know many strange tales hidden in the hearts of men and women who have stepped into the shadows.” This is also the case with the eponymous narrator of The Mysterious Traveler, who arrives by midnight train to the cue of that loneliest of sounds, the wail of a locomotive, to relate the misfortunes of those detoured into a strange and terrifying night world. |

The Unsuspected (film, 1947) with Jack Lampert.

The Power of the Whistler (film, 1945). |

|

A radio noir of particular note is the anthology Lights Out (1934– 1947), which thrived on placing its listeners inside the heads of the unbalanced and the fear-stricken. Wyllis Cooper, who created the series, and Arch Oboler, who later took over as head writer, pioneered a variety of expressionistic aural tactics (overlapping first-person voiceovers, booming voices from the dead) and complex narrative designs (extended flashbacks, dreams within dreams), all techniques later identified with film noir, to expose the tattered psyches of their characters. This “imagery” of sound yielded some truly unsettling set pieces, like a creeping mist that emerges from the night to turn people inside out, or a condemned murderer describing, in grave detail, the process of his own execution. Lights Out is testimony to the power of sug- gestion—the gripping dread of sitting alone in the dark—aided in no small part by the bond between the medium and the public. The radio listener, Oboler observed, “was as close to the performer as the microphone was to the performer.”

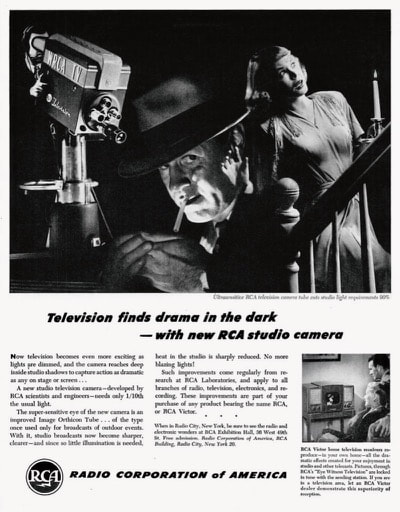

In 1946, when NBC first brought Lights Out to television, this intimacy was translated into the video close-up, and the whisper into the ear of the rapt radio listener evolved into the piercing gaze of the video actor that greeted the transfixed viewer. “First Person Singular” (1946), the first Lights Out to air, was adapted by Cooper from one of his radio scripts and directed by future-legend Fred Coe. It takes us inside the head of a loser (Carl Frank) who strangles his nagging wife (Mary Wilsey) on a sweltering summer night when the whole town seems ready to blow. The wife-killer is never shown: what he sees and hears as he contemplates and carries out his crime, and is then hanged for it, is entirely conveyed through a first-person camera. This subjective mode, with its necessarily limited perspective, amplifies the air of claustrophobia and inescapable fate to offer a heightened reality crucial to the noir style. Six months after this broadcast, cinema-goers would marvel at the same use of subjective camera in Lady in the Lake (1947), a film noir directed by Robert Montgomery. Many early television noirs utilized the subjective possibilities of the live video feed. In Volume One (ABC, 1949), a six-part series produced and written by Cooper, the camera is made an active participant. Its premiere installment, “No. 1,” offers an unsettling exercise in voyeurism in which the television frame doubles as the mirror over the bureau in a cheap hotel room. Floyd (Jack Lescoulie) and Georgia (Nancy Sheridan) have holed up there after robbing a bank. A great deal of their nervous bickering is played directly to the viewer, such as when Georgia nervously fusses with her lipstick in stark concave close-up, as if to destabilize the viewing experience. Or when Floyd, under mounting pressure, excitedly charges that he feels he’s being spied upon and accusingly swings at the camera-mirror—leaving a crack on our TV screen. Everything has gone wrong for these criminals, and in the end they’re simply swallowed by the camera-mirror, an indefinite conclusion that undoubtedly left viewers groping for a plausible explanation. At this juncture, with television on the verge of becoming a national enterprise, such narrative adventurousness was applauded. “This may be the program television has been waiting for to show those potentialities inherent in video which no other medium can duplicate,” proclaimed Billboard. “A mood of tension and growing terror was unquestionably abetted by the stark set and the use of nearly shrill black and white light and shadow effects.” The chiaroscuro imagery of Volume One and other live video noirs was made possible by the introduction in 1946 of the Image-Orthicon, a television camera requiring a mere foot-candle of light for exposure. Scenes demanding expressive atmospherics could now, as its developer RCA proclaimed, successfully “be illuminated only by a match flame or a lit cigarette.” Along with promoting a low-key style, the Orthicon, with its superior pictorial definition, changed the way television itself was perceived. The cinema may have had its broader canvas, its larger-than-life pictures, but the Orthicon delivered a life- like experience. Coupled with high-fidelity FM sound, dramas staged before the hungry eye of the Orthicon were delivered to the viewer without any distortions, interferences, or interpretation. Moreover, the intimate scale and sense of simultaneity attendant to viewing a live production served to psychologically bind the audience to the actors and the story. |

Publicity still for Lights Outs (radio, ca. 1938).

Advertisement for Image-Orthicon, RCA (1946).

|

Abridged from TV Noir by Allen Glover. Published by Abrams Press. All rights reserved.