TV Noir |

LIVE NOIR

|

The Anthologies

“Television is at its best when it offers us faces, reactions,

explorations of emotions registered by human beings.”

✦ HORACE NEWCOMBE

explorations of emotions registered by human beings.”

✦ HORACE NEWCOMBE

|

In “Un nouveau genre ‘policier’: L’Aventure criminelle” (1946), Nino Frank, the French critic who defined film noir, identified his grouping of dark narratives as being fixated with “the faces, the behavior, the thoughts—consequently, the trueness to life of the characters.” This attentive- ness to the messy, hard truths of modern living is equally fervent in the live dramatic anthologies that flourished on American television from the late 1940s to the early 1960s. Beginning with Kraft Television Theatre (1947–1958), the presentation of a weekly play brought to the masses through corporate largesse proved to be a necessary boon to the economic and creative development of the medium. As the number of television households swelled—from less than two hundred thousand in 1947 to twelve million in 1951—industrial titans like Westinghouse, Philco, Goodyear, Ford, Lux, Lucky Strike, Armstrong, and U.S. Steel readily signed on. Buy our pre-sliced cheese and tomorrow-world appliances, our miracle tires and electric shavers, went the reasoning, and we’ll keep that box in your living room flickering with drama— one week the tragedy of a sociopathic policeman, the next a downbeat chronicle of a self-loathing butcher.

The live anthologies favor the flawed, fraying hero, a man under the wheel; their predominant conflicts are those of personal crisis—the moral dilemmas brought on by unsatisfied urges and overreaching aims; the quagmires exposed by sudden shifts in the currents of fate. Their protagonists tend to suffer and struggle, sometimes even bleed; things rarely end well. In much the same way that the classic cycle of film noir, despite accounting for a mere slice of 1940s Hollywood output, has come to embody the zeitgeist of its era, it’s the mordantly toned, angst-driven productions that graph the ethos of “golden age” live television— plays like “Patterns” and “Crime in the Streets” and “A Man is Ten Feet Tall,” to name three from 1955, a peak year for the anthologies. These and other live noirs put forth a critical vision of mid-century America that both complements and overlaps the one purveyed by film noir, only they do so in brazen juxtaposition to the optimistically jingled sales pitches that paid for their broadcast. Where the earlier wave of live drama (e.g. The Black Angel) was presented commercial-free, and allowed to run at odd lengths, the introduction of advertising altered the rules of how a drama was to be constructed for television: the development of exposition and character, the ratcheting of suspense and tension, the placement of revelation and resolution were now at the service of “a word from our sponsor.” This restrictive model, with its specific act breaks, each building to a critical point, swelled a vibe that was already heady. The anthologies began staking space on network schedules at a time when dramatic standards were evolving. The element of life-born trueness that Frank singled out when describing his concept of film noir was gaining traction across all arts, from the street photography of Weegee and Robert Frank to the Method acting taking root in the New York theatre scene. This realist, psychologically oriented approach found a particularly receptive arena in live television. In 1952, Edward Barry Roberts, the script editor for Armstrong Circle Theatre (1950–1963), wrote of how “the unique quality of television is its revelation of character in quick, intense touches. Television, with its immediacy, gets to the heart of the matter, to the essence of the character, to the depicting of the human being who is there, as if under a microscope.” A story unfolding in the “now” only enhanced the existential aspect so vital to the noir style. Sweltering, claustrophobic sets, stark black-and-white imagery, roving, probing camerawork, and close-up after close-up of sweaty, anxious faces coalesced to create a personalized atmosphere of dis- quietude and imminent chaos. “If this technique of penetrating the mind is a familiar one in the films,” wrote New York Times critic Jack Gould in 1949, “it is a new experience when it comes in the stillness of one’s own living room.” Gould was particularly taken with how the medium had turned its supposed limitations of scale and size to a singular advantage, beginning with a three-camera system that al- lowed for uninterrupted performance—a fluidity not possible in film. In favoring actuality over montage, live drama revised the vocabulary of moving-image storytelling. And what it lacked in panorama it made up for in depth: its scope went inward rather than outward. The wide-angle lens, a necessity because of the close quarters (converted radio studios) in which the early anthologies were made, became the go-to looking glass, resulting in a deep-focus perspective well-suited to narratives centered on inner distress. |

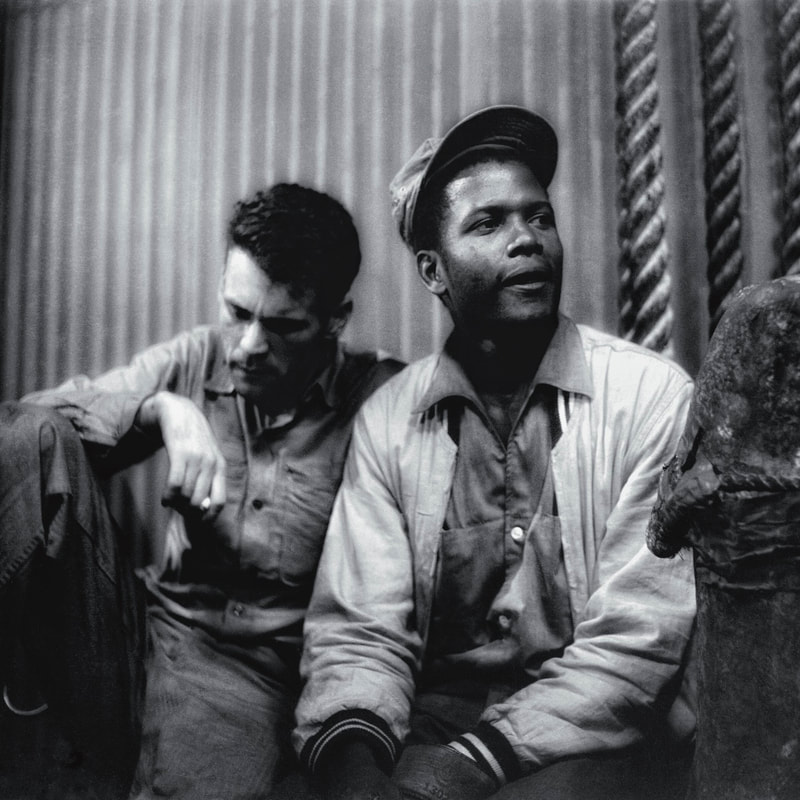

A Man Is Ten Feet Tall (Philco TV Playhouse, 1955)

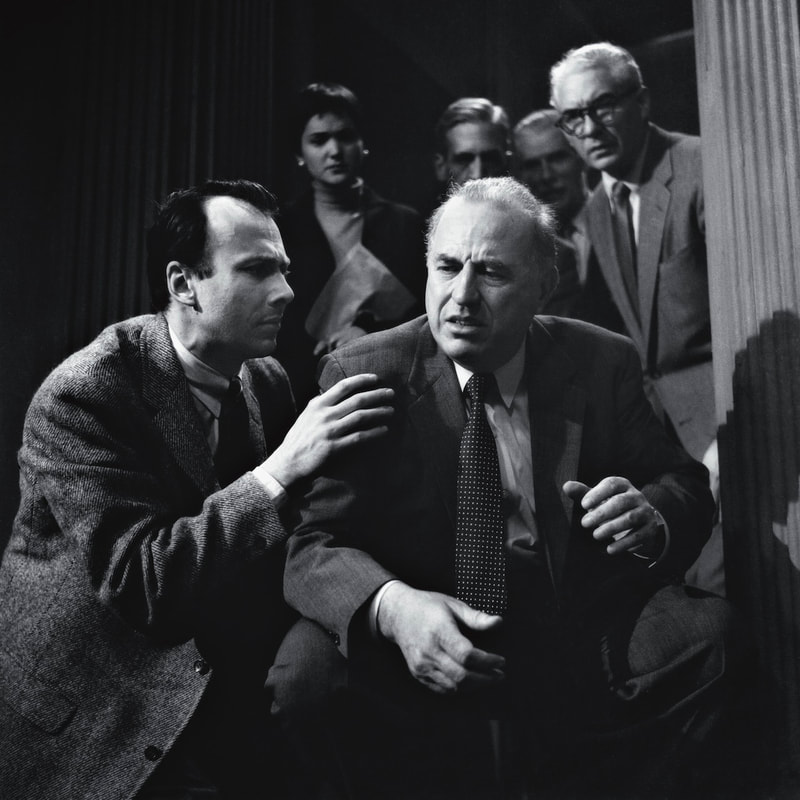

with Don Murray and Sidney Poiter. Crime in the Streets (Elgin Hour, 1954)

with John Cassavetes and Robert Preston. Patterns (Kraft Television Theatre, 1955) with Richard Kiley and Ed Begley.

|

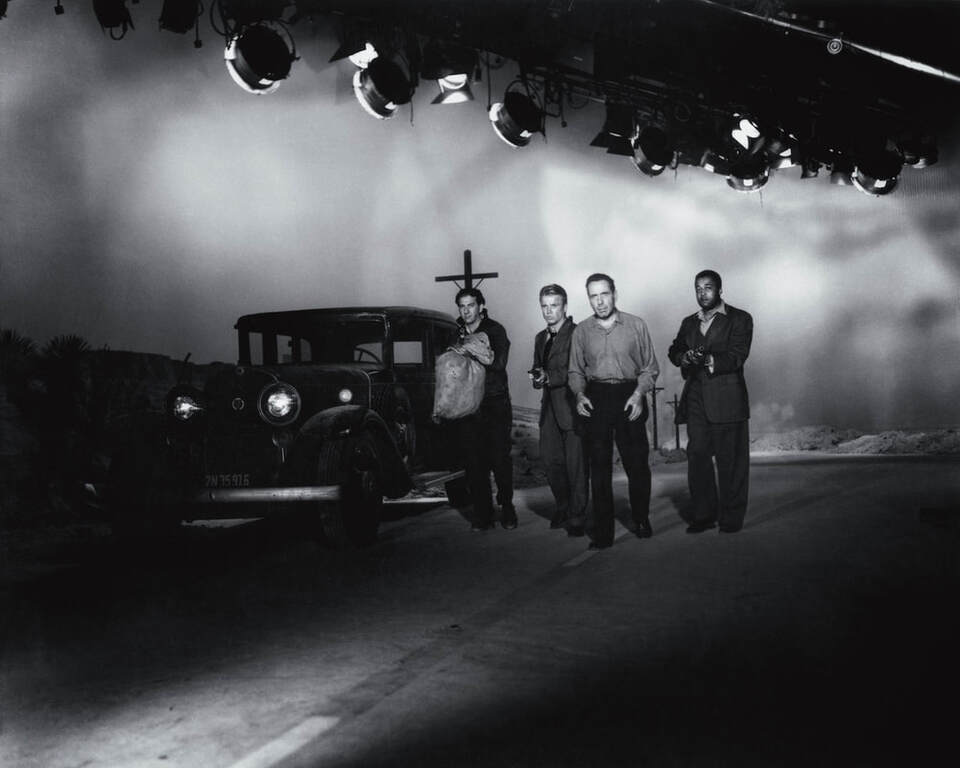

On the set of The Petrified Forest (Producer’s Showcase, 1955) with Jack Klugman, Richard Jaeckel, Humphrey Bogart, and Paul Hartman.

“We deal exclusively with crime melodrama, involving recognizable people.“

✦ MARTIN MANULIS, producer on SUSPENSE

✦ MARTIN MANULIS, producer on SUSPENSE

Danger, The Web, and Suspense (1949–1954) formed a troika of half-hour anthologies on CBS known as “The Three Weird Sisters.” Like Lights Outs (1949–1952) and The Clock (1949–1952) on NBC, or Hands of Murder (1949–1951) on DuMont, their domain was that of the psychological mystery- melodrama; such hour-longs as The Trap (aka Sure as Fate, 1949–1951) and Moment of Fear (1960) belong here as well. In contrast to the “prestige” anthologies, with their alternating-genre format, the "specialty" anthologies thrived on generic consistency. While each week brought a turnover in plot and characters, the overriding architecture remained bound to the thematic determinant promised in the title. Viewers tuning in to The Clock could expect a mystery involving “the inevitable penalties of time.” On The Web, CBS’s standing requirements for the writers stipulated “a sympathetic central character caught in a web of fate or dangerous circumstances of crime.”

The concept of fate, as practiced in noir fiction, is integral to the specialty anthologies. To varying degrees, each plies the notion that some ineffable force—chance, destiny, dumb luck—is silently at work, steering human ants down blind alleys. The prototypical specialty plot functions as a fable. A dreadful act is committed and concealed, only to be exposed through an ironic twist; the wrong-doer, brought to unanticipated comeuppance (confession, handcuffs, dis- grace), is left to decry the intrusion of “fate” in an otherwise surefire scheme.

One early episode of The Clock tells of a clerk, already up to his neck in adultery and blackmail, who strangles his employer, cleans out the office vault, fakes his death, and hires a plastic surgeon to carve him a new face. Transformed from a sneaky, miserable menace into an anonymous, wealthy one, he flits guilelessly about until the day he’s swept up in a random police dragnet. Unwilling to disclose his whereabouts on the night of his surgery, he finds himself charged with murder—his own. In these and other stories, a quantum of presumed guilt, an original sin, is a foundational necessity. That no indiscretion stays hidden for long is, of course, axiomatic to noir. But running parallel to the trope of a past that’s never far behind is the equally trenchant one of a future that’s all used up. Free will, the capacity to choose x or y, is merely the instrument with which to paint a fatal target on one’s back.

“Revenge” (Suspense, 1949), from Woolrich’s 1943 novel The Black Path of Fear, begins with a happy-seeming man and woman stepping off a boat in Ha- vana. No sooner have they taken in their first nightclub when she is fatally stabbed and he, to his surprise, is left holding the bloodied knife. Off he dashes, our hero, Scott (Eddie Albert), blamed for something he can’t even begin to comprehend. Woolrich starts here, with the stamp of guilt, the flight through dark, unfriendly streets, before rewinding several months to explain how Scott, penniless and adrift, came to be the chauffeur of a Miami gangster. Smitten with the boss’s wife, he ran away with her; their first night alone, clinging to one another in the hot Cuban air, was also their last.

Abridging a narrative as dense and fractured as this for a half-hour teleplay involved distilling the story to its situational essence while also molding it to accommodate the obligatory commercial, a formula CBS’s guidelines for the “Weird Sisters” outlined as “a two-act structure with a cliff-hanger middle-break.” “Revenge” hits this point with Scott, blood on his hands and the hollering police at his heels, rounding a corner and reaching a dead end. Woolrich writes: “Two doorways in a darkened alley; one spelled life and one spelled death.” Only via the “correct” door does Scott extend his adventure long enough to find someone with the wits to extract him from this mess.

A system of gateways and passages is important to a noir story: the prevalent iconography of winding stairwells and lonely streets goes lock-and-key with the labyrinthine plots. No other storytelling mechanism places such stress on causality, on the consequences of crossing literal and figurative thresholds. even the most insignificant of actions can spell catastrophe; conversely, in turning one knob but not the other, hapless night-dashers like Scott can temporarily sidestep their inevitable reckoning. Woolrich’s confused and lost fool is typical of noir’s loser- heroes in that he retains complicity in misfortune. For these types, acting out, indulging desires or convictions, is an invitation for fate to sling its arrow. (Conformity, in this era, was a virtue on par with patriotism, regular church attendance, and a solid corporate job.) Were Scott to have kept his lust in check, he’d be safely back in Miami, scrubbing the boss’s cars. Had the clerk in The Clock resisted the temptation to violate the vault, he might have avoided the conundrum of having to confess to one crime to prove his innocence in another.

The moral promoted by these fables is as conservative as it is cardinal: to err from the straight and narrow is to steer oneself headlong into the nightmare. Hence the title sequence of portending doom with which each Danger begins: a careening POV shot of a threatening highway at night in which the program title whizzes by as an unheeded sign. Noir fatalists like Woolrich and David Goodis built their canons describing the pitfalls awaiting those who travel dark roads with false impunity. Goodis, in his novel Cassidy’s Girl (1951), paints his luckless protagonist’s struggle to avoid the abyss in language familiar to any viewer of Danger: “keeping his eye on the road and his mind on the wheel was a protective fence holding him back from internal as well as external catastrophe.” In programs like The Web or The Clock, the barrier has likely already been hedged; in others, especially Hands of Murder, it’s usually a pushing influence, a mitigating circumstance, which drives the protagonist over. What distinguishes one from the other is simply at what chapter in the downfall of a man (very rarely a woman) the story initiates.

The concept of fate, as practiced in noir fiction, is integral to the specialty anthologies. To varying degrees, each plies the notion that some ineffable force—chance, destiny, dumb luck—is silently at work, steering human ants down blind alleys. The prototypical specialty plot functions as a fable. A dreadful act is committed and concealed, only to be exposed through an ironic twist; the wrong-doer, brought to unanticipated comeuppance (confession, handcuffs, dis- grace), is left to decry the intrusion of “fate” in an otherwise surefire scheme.

One early episode of The Clock tells of a clerk, already up to his neck in adultery and blackmail, who strangles his employer, cleans out the office vault, fakes his death, and hires a plastic surgeon to carve him a new face. Transformed from a sneaky, miserable menace into an anonymous, wealthy one, he flits guilelessly about until the day he’s swept up in a random police dragnet. Unwilling to disclose his whereabouts on the night of his surgery, he finds himself charged with murder—his own. In these and other stories, a quantum of presumed guilt, an original sin, is a foundational necessity. That no indiscretion stays hidden for long is, of course, axiomatic to noir. But running parallel to the trope of a past that’s never far behind is the equally trenchant one of a future that’s all used up. Free will, the capacity to choose x or y, is merely the instrument with which to paint a fatal target on one’s back.

“Revenge” (Suspense, 1949), from Woolrich’s 1943 novel The Black Path of Fear, begins with a happy-seeming man and woman stepping off a boat in Ha- vana. No sooner have they taken in their first nightclub when she is fatally stabbed and he, to his surprise, is left holding the bloodied knife. Off he dashes, our hero, Scott (Eddie Albert), blamed for something he can’t even begin to comprehend. Woolrich starts here, with the stamp of guilt, the flight through dark, unfriendly streets, before rewinding several months to explain how Scott, penniless and adrift, came to be the chauffeur of a Miami gangster. Smitten with the boss’s wife, he ran away with her; their first night alone, clinging to one another in the hot Cuban air, was also their last.

Abridging a narrative as dense and fractured as this for a half-hour teleplay involved distilling the story to its situational essence while also molding it to accommodate the obligatory commercial, a formula CBS’s guidelines for the “Weird Sisters” outlined as “a two-act structure with a cliff-hanger middle-break.” “Revenge” hits this point with Scott, blood on his hands and the hollering police at his heels, rounding a corner and reaching a dead end. Woolrich writes: “Two doorways in a darkened alley; one spelled life and one spelled death.” Only via the “correct” door does Scott extend his adventure long enough to find someone with the wits to extract him from this mess.

A system of gateways and passages is important to a noir story: the prevalent iconography of winding stairwells and lonely streets goes lock-and-key with the labyrinthine plots. No other storytelling mechanism places such stress on causality, on the consequences of crossing literal and figurative thresholds. even the most insignificant of actions can spell catastrophe; conversely, in turning one knob but not the other, hapless night-dashers like Scott can temporarily sidestep their inevitable reckoning. Woolrich’s confused and lost fool is typical of noir’s loser- heroes in that he retains complicity in misfortune. For these types, acting out, indulging desires or convictions, is an invitation for fate to sling its arrow. (Conformity, in this era, was a virtue on par with patriotism, regular church attendance, and a solid corporate job.) Were Scott to have kept his lust in check, he’d be safely back in Miami, scrubbing the boss’s cars. Had the clerk in The Clock resisted the temptation to violate the vault, he might have avoided the conundrum of having to confess to one crime to prove his innocence in another.

The moral promoted by these fables is as conservative as it is cardinal: to err from the straight and narrow is to steer oneself headlong into the nightmare. Hence the title sequence of portending doom with which each Danger begins: a careening POV shot of a threatening highway at night in which the program title whizzes by as an unheeded sign. Noir fatalists like Woolrich and David Goodis built their canons describing the pitfalls awaiting those who travel dark roads with false impunity. Goodis, in his novel Cassidy’s Girl (1951), paints his luckless protagonist’s struggle to avoid the abyss in language familiar to any viewer of Danger: “keeping his eye on the road and his mind on the wheel was a protective fence holding him back from internal as well as external catastrophe.” In programs like The Web or The Clock, the barrier has likely already been hedged; in others, especially Hands of Murder, it’s usually a pushing influence, a mitigating circumstance, which drives the protagonist over. What distinguishes one from the other is simply at what chapter in the downfall of a man (very rarely a woman) the story initiates.

Abridged from TV Noir by Allen Glover. Published by Abrams Press. All rights reserved.