TV Noir |

A CLASSIC CYCLE

|

Dragnet |

NBC 1951 — 1959

|

“This is the city. Los Angeles, California. I work here. I'm a cop.” ✦ JOE FRIDAY

|

Through the 1950s, the unsmiling jug-eared mug of Jack Webb was the emblem of American justice. Each week, as Sgt. Joe Friday, he plodded through Los Angeles, coaxed its murderers and petty thieves from filthy rented rooms and sad corner taverns, and made them face their crimes. It was a never-ending cycle of transgression and banishment—a circular lesson in how society’s miscreants are identified, captured, and convicted. Friday rarely used his gun; words, sparsely uttered but always to the point, were his weapon of choice. In crafting Dragnet for radio (1949–1955), and then transferring it to television, Webb took inspiration from the bulging files of the LAPD, with whom he worked closely in recreating the tedious, methodical routine of police procedure. eschewing pulpy melodrama for prosaic authenticity, he made the real City of Angels, in all its blistering sin, an integral part of the proceedings. Its inhabitants, collated by degrees of culpability, formed a human mosaic of crime in the big city. Los Angeles emerged as a place of eternal chaos contained, but only barely, by the quiet, grinding persistence of Joe Friday.

Each Dragnet launches with a proclamation of authority: an image of Friday’ sergeant’s badge (no. 714) accompanied by Walter Schumann’s emphatic four-note motto (“dum-de- dum-dum”), an introduction equally foreboding and reassuring. The police, personified by Friday, are good. The criminals are bad, if often compelling. It’s all, we’re told, true: “Only the names have been changed to protect the innocent.” Thusly framed, the story is handed over to Friday, through whom we learn how police evidence is accrued. “We use the old-fashioned, plain way of reporting, where you don’t know any more than the cops do,” Webb explained. “It makes you a cop and you unwind the story.” Through false leads, dead ends, detours to the morgue, the hall of records, the crime lab, Friday, who narrates as if reading from a police blotter, takes us through a case. Some are solved in hours; others drag on for months. With each Friday exposes another rotten fact-piece of the city and its people. The TV critic John Crosby once wrote of Dragnet: “An investigation of crime, if it is as pitilessly honest as this program, is frequently an investigation into man’s deeper motives, crime simply being the more violent aberration of the urges we all possess.” Dragnet’s stories climax not with a triumphant hail of gunfire, or even with the obligatory slapping on of hand- cuffs, but with a peeling back of lies and bluster to get to the ugly truths at the heart of the chaos, so that the appropriate punishment may be meted. The specifics are then relayed over an image of the culprit glumly posing for a mug shot as a sentencing is spelled out: Lester Zachary Wylie, child molester, “now serving his term in the State Penitentiary, San Quentin, California” (“The Big Crime”). Or Henry Elsworth Ross, serial killer, “executed in the lethal gas chamber” (“The Big Cast”). After this, a pair of hands bearing a chisel and a hammer bang out the logo for Mark VII, Webb’s production company, sealing the case with a clang of finality. Given the moral stridency inherent in such a formula, Dragnet would appear to reject a noir sensibility. Yet its portrait of an LA teeming with alienated, grasping souls suggests otherwise. Because its stories are drawn from closed files, many of them dating back decades, the city on display is much like the one written about by Raymond Chandler and Horace McCoy, and even more like the one in which Webb came of age during the Depression, sickly and fatherless. Growing up in Bunker Hill, a neighborhood of “epic dereliction . . . the rot in the heart of the expanding metropolis,” as social historian Mike Davis has described this since-razed patch of downtown, Webb shared a single-room flat with his mother and his grandmother. Public relief put food on the table and shirts on his back. The squalid conditions of his upbringing are reflected throughout a vision of Los Angeles as an environment of hardship and desperation. “The bums, priests, con men, whining housewives, burglars, waitresses, children, and bewildered ordinary citizens who people Dragnet seem as sorrowfully genuine as old pistols in a hockshop window,” said Time magazine in a 1954 cover piece. “By using them to dramatize real cases from the Los Angeles police files—and by viewing them with a compassion totally absent in most fictional tales of private eyes—Webb has been able to utilize many a difficult theme (dope addiction, sex perversion) with scarcely a murmur of protest from his huge public.” Though Dragnet’s hustlers and smut peddlers, its smack fiends and killers, are invariably rounded up and put away, the dispensing of justice is hardly conclusive. Week after week, like Sisyphus, Friday returns to roll yet another suspect up the steps of City Hall. This pervasive sense of futility, coupled with the obsessive endeavor to defy it, affirms Dragnet as dire a work of noir as any. |

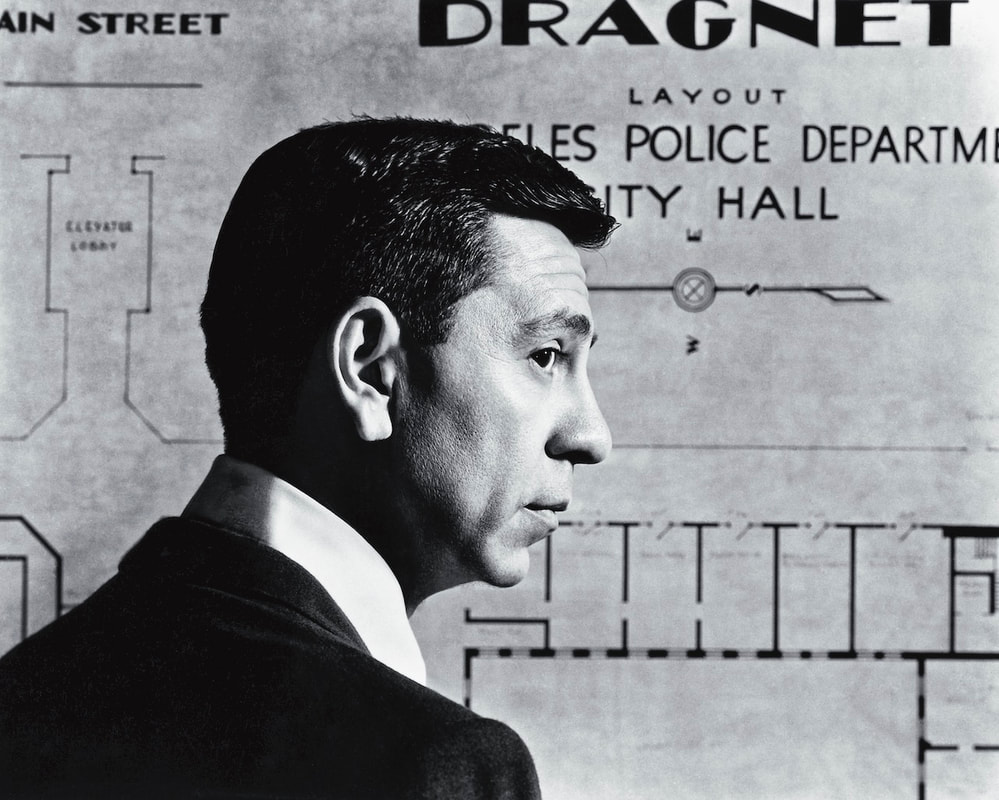

Jack Webb in the Dragnet production office (ca. 1954). On the Disney lot in Burbank, he constructed a full-scale replica of the LAPD’s headquarters at City Hall, accurate to the locks and doorknobs (cast from plaster molds of the originals), the dents in the walls and the stains on the floors, and the extension numbers pasted on every departmental telephone.

A novelization of Dragnet (Whitman, 1957).

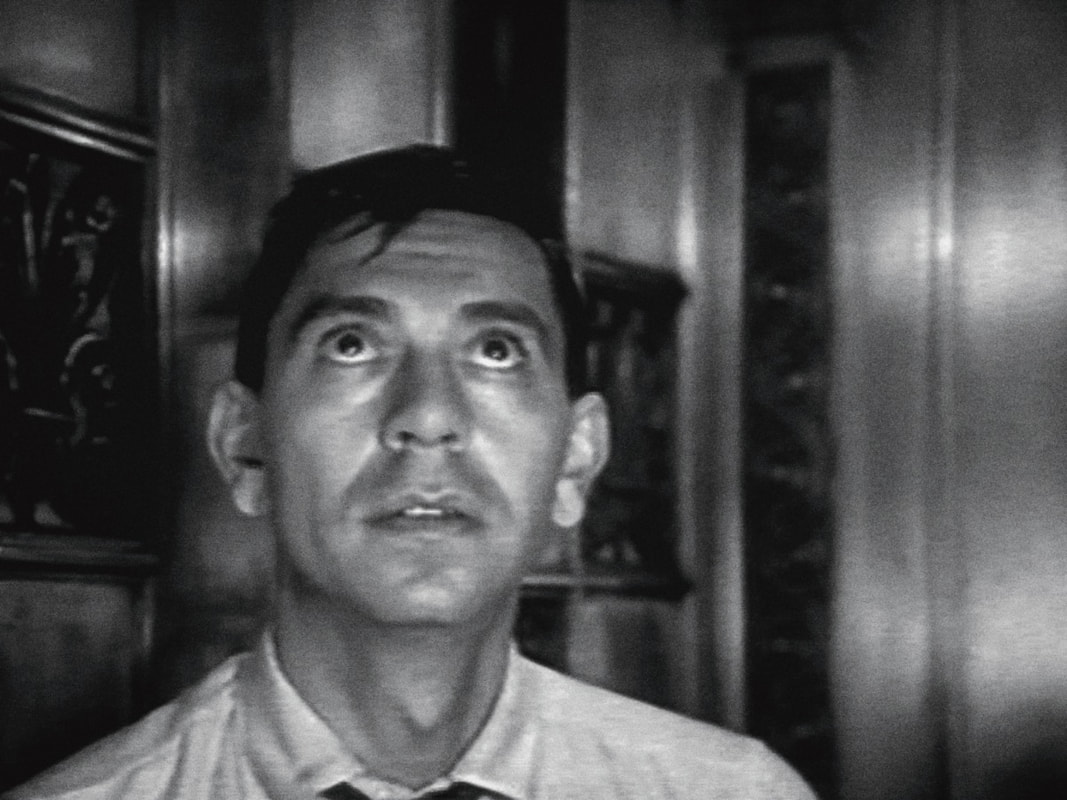

Jack Webb in the series pilot:

The Human Bomb (Chesterfield Sound-Off Time, 1951). |

Abridged from TV NOIR by Allen Glover. Published by Abrams Press. All rights reserved.