TV Noir |

NEO NOIR

|

The Loner |

CBS 1965 – 1966

|

“In the aftermath of the bloodletting called the Civil War, thousands of rootless, restless, searching men traveled west. such a man was William Colton. like the others, he carried a blanket roll, a proficient gun, and a dedication to a new chapter in American history: the opening of the West.”

✦ OPENING NARRATION, The Loner

✦ OPENING NARRATION, The Loner

|

Our first impression of William Colton is this Western from Rod Serling is of a solitary figure on horseback pitted against a barren landscape. It’s an image synonymous with the myth of the American West—a myth already in the making, in countless dime novels and roadshow spectacles, before the frontier was fully claimed. The white, conquering male of the West is brave, independent, resilient; but also restless, alienated, and violent. As the myth moved into and through the twentieth century, filtered through countless stories, songs, films, and television shows, its standards of heroism became shaded. Serling’s Colton, played by Lloyd Bridges, is a hero of virtue and honor, but he’s also melancholic and disillusioned—an existential gunman. Sick of war, of blood and fighting, he’s resigned his commission in the Union cavalry and disappeared westward, “to get the cannon smoke out of my eyes, the noise out of my ears, maybe some of the pictures out of my head.” That urge to hit the open road, the need to see what lies over the next hill, while in its own right uniquely correlated to American notions of individualism, is also a part of the Western mythos, one that will be key to this loner’s journey.

Serling conceived The Loner in 1960 just as he was finishing what he thought to be his first and only season of The Twilight Zone. The so-called “adult Western” was at the height of its popularity; the anthology drama, Serling’s metier, was all but finished. His one-hour pilot script about a nomadic veteran known as “The Loner” combined aspects of both. With The Twilight Zone gaining an unexpected reprieve, Serling stuffed his script in a drawer. He was on a speaking tour of Asia in early 1965 when he received a cable- gram: due to a schedule shift, CBS needed a half- hour lead-in to its beloved perennial Gunsmoke (1955–1975). Might Serling be able to reformat his “Loner” concept in time for the upcoming season? So quickly was the series rushed into production that CBS apparently neglected to read Serling’s pages. Expecting something in the vein of their other new oater that season, The Wild Wild West (1965–1969)—“chases, running gun battles, runaway stage coaches,” as one network executive put it—they were aghast when Serling delivered a horse of a different feather, if not an entirely different Wild West. Even by the dark standard of a work like The Searchers (1956), Serling’s take on the genre is unremittingly downcast. Though set, like John Ford’s picture, in “the aftermath of the bloodletting called the Civil War,” its despairing worldview is more in tune with that purveyed by the classic cycle of film noir, itself “a cinematic style forged in the fires of war, exile, and disillusion, a melodramatic reflection for a world gone mad,” as Tom Flinn writes in “Three Faces of Film Noir” (1972). Like the displaced veterans of The Blue Dahlia (1945) and Ride the Pink Horse (1947), Colton is a rootless, damaged male uncertain of his role in a postwar society. Serling, himself a veteran of World War II, knew something of this: “I was traumatized into writing by war events, by going through a war in a combat situation and feeling the desperate need for some sort of therapy—get it out of my gut, write it down.” The cure, for Colton, is itinerancy: a trusty steed and an open trail. Wised up to the absurdity of resolving conflict through violence, he seeks what Richard Schickel, in a 1965 essay (“everything’s Coming Up Loners”), described as “a viable present, some place where he won’t be expected to kill people.” The contradictions at play in The Loner are made evident in its narrated prologue. Though Colton carries “a proficient gun,” he’s averse to gunplay; while sensitive to inequality, to the suffering of others, he’s among the ranks of those dedicated to “the opening of the West,” a euphemism for the bloody campaign of expansionism wrought by American manifest destiny. Within these apparent inconsistencies, Serling stretches the mythos of the West to accommodate his own concerns about mankind’s propensity for destruction. “For civilization to survive,” he tells us in one of his Twilight Zone voiceovers, “the human race has to remain civilized” (“The Shelter,” 1960). But the laws and structures that hold society together in the urban east are largely absent in the vacant West. Colton, a career military officer, a graduate of West Point, straddles these realms uneasily. On the one hand, because the Western demands its heroes be straight shooters—marksmanship being an exemplar of ethical code—Colton goes nowhere without his gun strapped to his side. (His very name evokes nineteenth-century gunsmith Samuel Colt.) On the other, as a Serling protagonist, a hero of moral imperative, he prefers mediation through verbal discourse. He’s a voice of decency, the standard against which the actions of others are judged. |

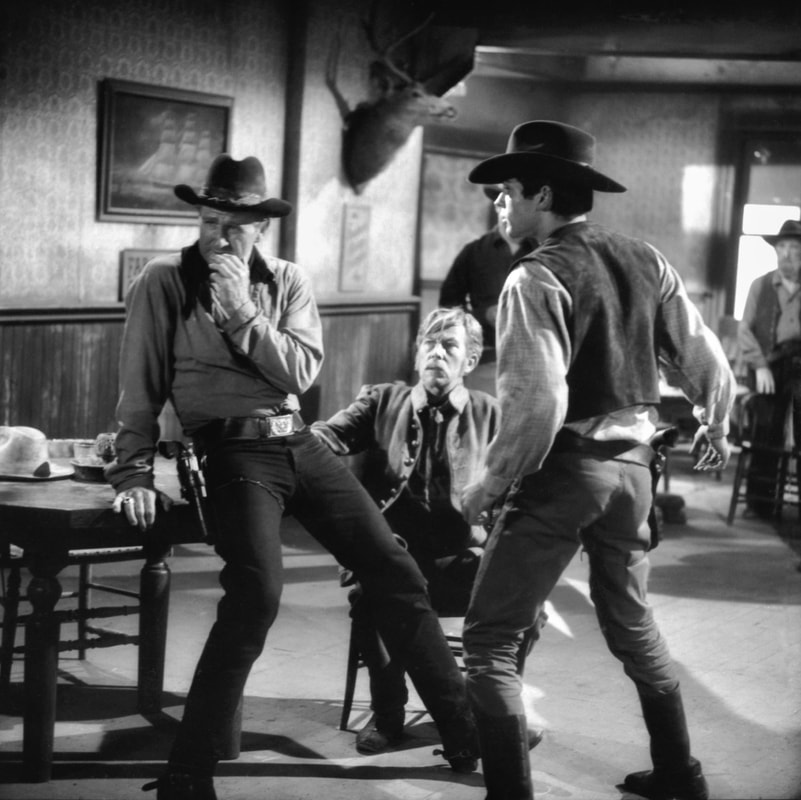

Promotional still for The Loner with Lloyd Bridges (1965).

An Echo of Bugles (The Loner, 1965)

with Lloyd Bridges, Whit Bissell, and Tony Bill. On the set of The Homecoming of Lemuel Stove (1965)

with Brock Peters and Lloyd Bridges. In his live anthology days, Serling twice tried to dramatize the 1955 lynching of Emmett Till only to find his resulting teleplays diluted by sponsor interference: “Use simple explanatory line indicating boy had gotten out of line and didn’t know his place,” the censors instructed. By the mid-1960s, with civil rights on the forefront of national discourse, Serling was able to tackle the subject overtly, yielding the startling central image of a black man hanging from a tree in a town square. The victim, an emancipated slave, is the father of a returning Union soldier whom Colton has befriended. Nearly everyone in town, they learn, had a hand in the lynching. |

Excerpted and adapted from TV NOIR by Allen Glover. Published by Abrams Press. All rights reserved.