TV Noir |

LIVE NOIR

|

The Detectives

|

“The story of the honest detective who thinks faster than the police and is maneuvered into impossible situations only to wiggle out just in time is a standard pattern in the movies and on the radio. Now the same theme is proving just as trustworthy on TV.”

✦ NEWSWEEK, 1949 |

|

|

A swirling cloud of smoke is as ubiquitous in noir as a creeping shadow: both add to the dim and nihilistic atmosphere of a world burning from the inside. The nightclubs and salons of noir are filled with smoke, as are its precinct houses (discount cigarettes) and gangsters’ lairs (imported cigars). Marlowe smoked, as did Spade; both were brought to the screen by Humphrey Bogart—hence the dangling “bogey” synonymous with the public image of the detective. It was because of associations like these that Big Tobacco, keen on appealing to the demographic that devoured crime fiction in its many forms (movies, radio, pulps, and paperbacks), became the primary sponsor of such early episodic noir as Man Against Crime (CBS, 1949–1953; NBC/DuMont, 1953–1954), Martin Kane, Private Eye (NBC, 1949–1954), and The Plainclothes Man (DuMont, 1949–1953). The detective genre, with its rote cycle of a case assumed, investigated, and solved, offered the ideal platform for the repetitive hawking of a product that was meant to be ignited, inhaled, and extinguished. Smoking represented ritual, and the ritual was parlayed into formula: a weekly whodunit.

The U.S. Tobacco Company, in assuming sponsorship of Martin Kane, Private Eye, felt strongly that its detective should be a pipe smoker and saw to it that a tobacco shop be written into the show, lest Kane ever find himself in a spot without a pouch of Old Briar, that “master mixture of rare flavor and aroma.” Though a cigarette smoker off-screen, William Gargan, who originated the role, proved himself adept at the courtly art of pipe stuffing; Lloyd Nolan and Lee Tracy, the actors who succeeded him, less so. Mark Stevens, the fourth and final Martin Kane, insisted his fix be wrapped in paper, like Joe Friday, a Chesterfield man. Over on Man Against Crime, a private-eye show bankrolled by R.J. Reynolds, Mike Barnett filled his ashtray with the butts of Camels; Ralph Bellamy, who played him, made a point of angling the pack on his desk for maximum camera exposure. Given that these shows were put on the air live, under excruciating pressure, the actors probably welcomed the license to smoke while working. Debuting a few weeks apart, Martin Kane, Man Against Crime, and The Plainclothes Man successfully introduced the episodic crime series, with its continuing hero, a solver of crimes, to television audiences. Their prototype is the Hammett-Chandler hardboiled mystery, ironed out to fit a half-hour slot, and then bisected with a commercial—a two-act paradigm already proven successful on radio. As the peddlers of tobacco saw it, an immediate splash of chaos was essential in retaining viewer interest through the first act and into the obligatory break. In a memorandum to the writers of Man Against Crime, the William Esty Agency, which produced the series for Reynolds, outlined the formula: “It has been found that we retain audience interest best when our story is concerned with murder. Therefore, although other crimes may be introduced, somebody must be murdered, preferably early, with the threat of more violence to come.” The detective-hero, though battered about, was to conclude his adventure triumphant and unscathed, his fingers, despite the beatings administered or endured, in reasonable enough working order to operate a Zippo for the closing plug. Attendant to its dramaturgical advice, the Esty Agency issued strict guidelines for the proper alignment of nicotine intake with heroic stature: “Do not have the heavy or any disreputable person smoking a cigarette. Do not associate the smoking of cigarettes with undesirable scenes or situations plot-wise.” Only Barnett, “defender of the oppressed and a fearless fighter for common justice,” was to enjoy the extra mildness, extra coolness, and extra flavor of a filterless Camel, preferably one after another. Likewise on Martin Kane smoking was a privilege reserved for the discerning professional: only Kane and the police smoke. Rather than stop the action for the sponsor’s message, the J. Walter Thompson Agency, which oversaw the show, simply integrated it into the plot. Halfway through each investigation, regardless of how muddled a puzzle he faces, Kane drops by Happy McMann’s tobacco emporium. “Boy, this one really is a humdinger,” Happy (Walter kinsella), a retired detective himself, will say as he chats up Kane. Commercials had quietly been a part of television since 1946; by 1949 they were overt—glad you’re enjoying the free show, now how about reconsidering your purchasing habits? Happy’s is also where Kane interacts with the police; depending on the Kane, this can be a fruitful encounter or a very unpleasant one. Often, Kane and the cops will move to the foreground to hammer out a theory between puffs, while Happy, back at his counter, can be heard extolling the virtues of his wares to a customer, resulting in a soundtrack that’s part expository patter and part smooth salesmanship. Because the timing of every Kane had to be accurate to the second, the writers allotted a search scene in the second act: if the show was over schedule, the actor would find the clue instantly; if it was running slow, he could rummage more carelessly. Man Against Crime deployed the same tactic. A live telecast introduced other perils: forgotten dialogue, “walking corpses,” wandering stagehands, visible microphones, electrical shortages, and so forth. In Martin Kane, when Lloyd Nolan slugs a fellow with his right hand while boasting of his “left hook,” we take it not as a line flub, but as the utterance of a man caught in the thrall of an uninterrupted performance. As Nolan’s successor, Lee Tracy, put it: “The good old adrenalin glands start working, and you’re operating on a rarefied plane.” Over on The Plainclothes Man, a live subjective-camera series for DuMont, Ken Lynch, who plays the titular Lieutenant, is never seen; rather, we see what he sees. His off-screen voice, occasional gestures, and near-constant stream of pipe smoke (Edgeworth Tobacco sponsored the show) guide us through each investigation. The primary camera, the one standing in for the Lieutenant, is set at eye level: when a body is splayed out on the floor, our view tilts down to reveal its twisted form. When the forensic boys hand over a coroner’s report, we read along, absorbing the grisly, typed-up facts—time of death, number of wounds, likely weapon. When the clues coalesce, and the Lieutenant finally corners his culprit, we’re confronted with a mean-looking mug glaring back, poised for confrontation or a hasty denial. Should someone take a swipe at the Lieutenant, a fairly common occurrence, a huge fist smashes into the lens. In lieu of a visible leading man, the Lieutenant’s second banana, Sgt. Brady (Jack Orrison), is the most familiar face. His gruff patter, delivered directly to the camera, reinforces the notion that we’re a central participant in the investigation at hand. But where a film noir like Lady in the Lake (1947) purveys an exclusively singular viewpoint, The Plainclothes Man lets in a little air. This isn’t completely “our” story: when the Lieutenant interrogates a criminal or takes a statement from a witness, the action cuts back in time to reveal, from a traditionally neutral perspective, the events being discussed. Through flashback, the bits and pieces of the ancillary narratives that add up to the crime being solved are put forth to be dissected and analyzed. As series director William Marceau explained, “the format is built directly around the fact that there is in all lovers of the detective story the subconscious desire to be a detective and actively share in the unraveling of clues.” The ritual of a mystery sparked, experienced, and finished would prove to be more enduring than anybody may have guessed. |

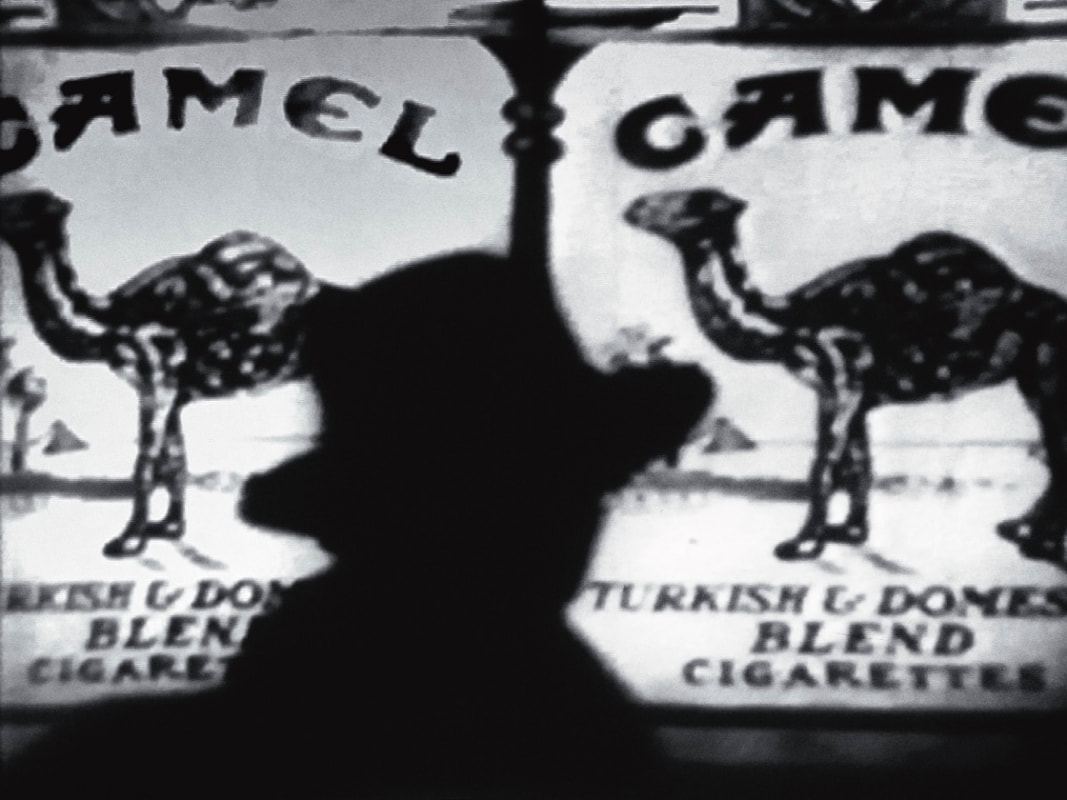

Title Card, Man Against Crime (1951)

The Plainclothes Man (1953).

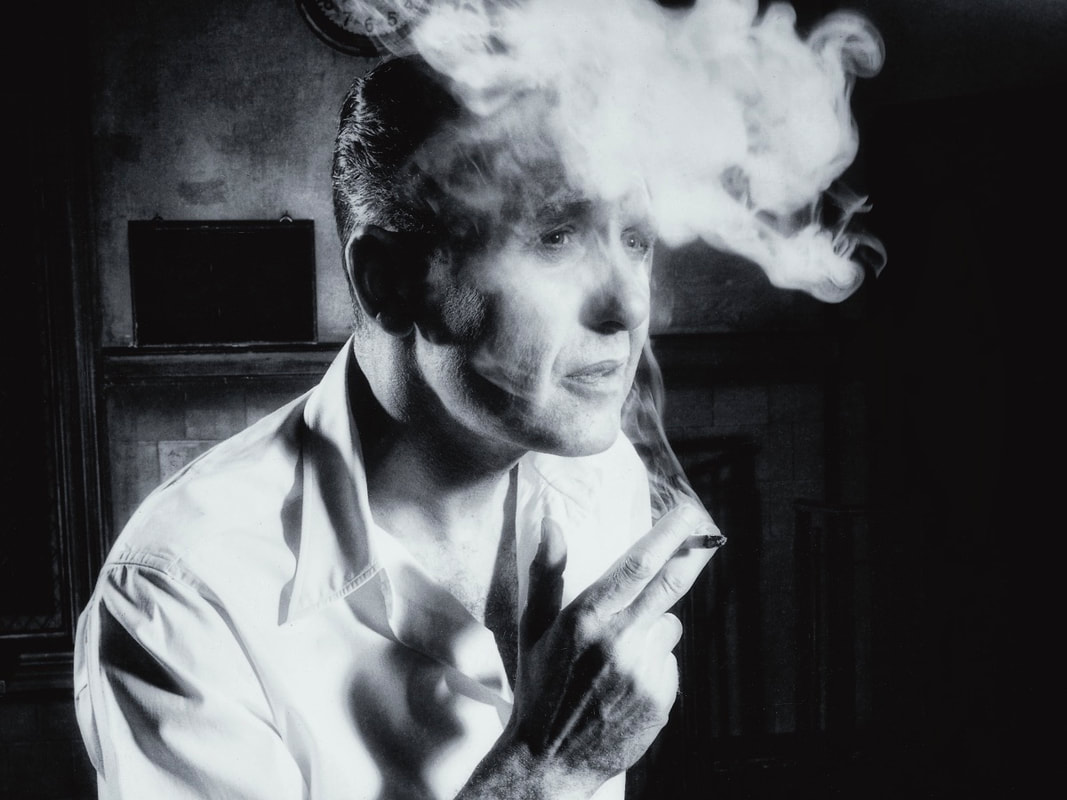

Publicity still for Detective Story (stage, 1949) with Ralph Bellamy.

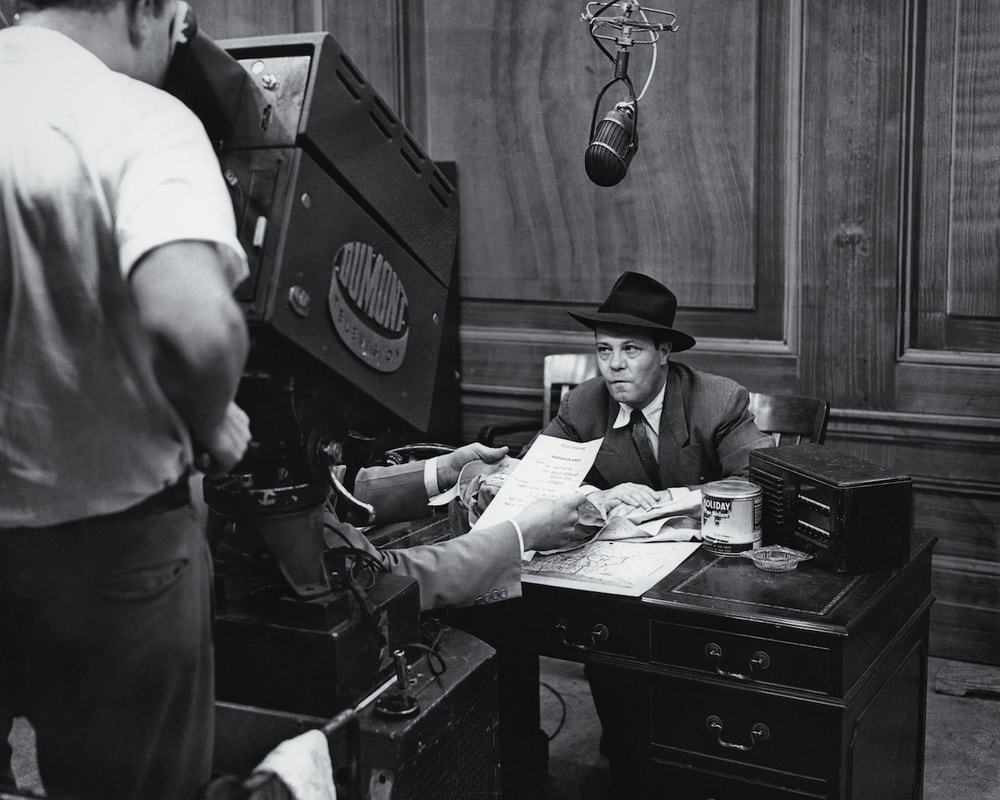

On the set of Martin Kane. Private Eye (1950).

On the set of The Plainclothes Man (1949) with Ken Lynch (obscured) and Jack Orrison. Excepting his hands, and the occasional plume of smoke, the hero of this subjective-camera series is never seen: “Unknown, unsung, but always on guard, protecting you against crime,” explains the weekly narrator.

|

Excerpted and adapted from TV Noir by Allen Glover. Published by Abrams Press. All rights reserved.